Reconciliation Reflections: Six Student Projects

-

Historic Stairwell, Daniels Building

Historic Stairwell, Daniels Building

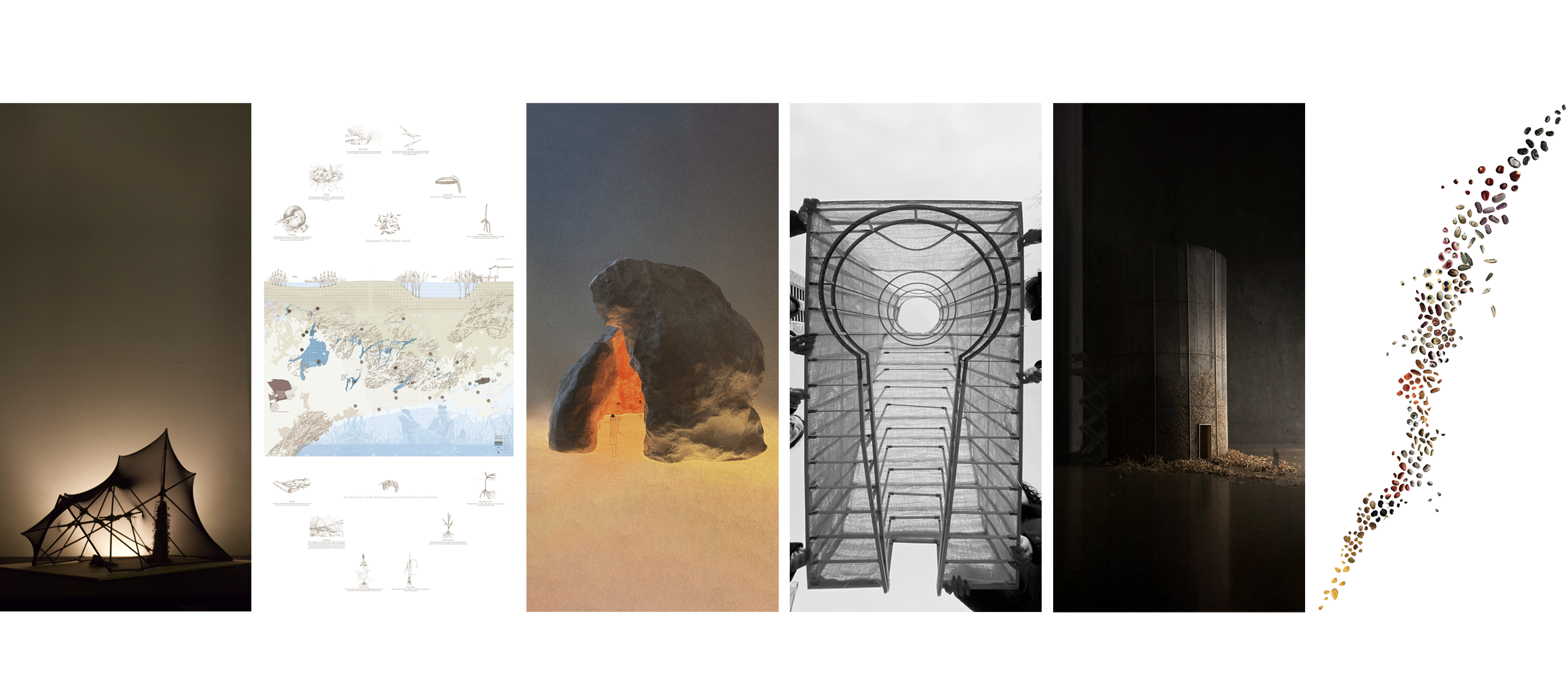

To mark National Indigenous History Month in June 2024, the Daniels Faculty will launch Reconciliation Reflections: Six Student Projects—a temporary installation of student work from two graduate studios developed in response to Wecheehetowin ‘Answering the Call’ University of Toronto–Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) Calls to Action.

The installation features projects from Architecture Studio 2: Site, Matter, Ecology, and Indigenous Storywork and Landscape Architecture Studio 2: Land(scape) and Memory—both studios aim to be concrete responses to Call 17 to integrate Indigenous curriculum content.

The six projects on view from the Master of Architecture and Master of Landscape Architecture programs were selected by the Daniels Faculty’s First Peoples Leadership Advisory Group: Amos Key Jr., Trina Moyan and Dorothy Peters.

Reconciliation Reflections will be on view in the Historic Stairwell Gallery to honour National Indigenous Peoples Day on June 21. The exhibition will remain through September for the National Month for Truth and Reconciliation and November for Treaties Recognition Week and Louis Riel Day.

Architecture Studio 2: Site, Matter, Ecology, and Indigenous Storywork

Architecture Studio 2 considers the concept of site and landscape as an action in reconciliation, ecology as a study in relationships that define inhabitation, and Indigenous storywork as a method of research and design-work.

With Crawford Lake as their site, students were asked to design a museum for Indigenous art that builds on the knowledge they gained through workshops and guest lectures on Indigenous cultural competency, ways of being, ways of knowledge, Indigenous cultural and design practices.

The four works on display in Reconciliation Reflections are group projects for the assignment "The Artifact and The Room," which involved the consideration of five contemporary artworks.

ARC1012 Studio Coordinator: Behnaz Assadi; Instructors: Chloe Town, Anne-Marie Armstrong, Mauricio Quiros Pacheco, Brian Boigon, Aleris Rodgers, Julia Di Castri. The syllabus for this studio was initially developed by Adrian Phiffer and James Bird (Knowledge Keeper of the Dënësųłinë́ and Nêhiyawak Nations and Residential School Survivor).

Landscape Studio 2: Land(scape) and Memory

Landscape Studio 2 introduces concepts, terminology, and design research tools for academic and professional work that requires attentiveness to cultural and political history, history telling, cultural practices, community engagement, multi-cultural collaborations, as well as the creation of spaces for ongoing public participation, dialogue, stewardship, shared governance, and civic expression.

The two works on display in Reconciliation Reflections were developed thorough engagement in three design research explorations: 1) Memory, Healing and Cultural Resurgence: Reconstructing the Counter Monument, 2) Land-Based Mapping: Visualizing Environmental Histories and Landscape Changes, and 3) Memory, Land Relations and Indigenous Futurisms: Imagining the University of Toronto as an Indigenous space.

LAN1012 Instructors: Liat Margolis, Terence Radford

Project Statements

1. “Resilience” by Issac Valle and Susan Xi (ARC1012)

The adverse effect of rising land costs has affected and participated in the explicit gentrification of the Indigenous peoples specifically in Vancouver, where Anishinaabe artist, Rebecca Belmore expresses her artwork, The Tower and Tarpaulin. Her art often symbolizes political, economic, and social issues facing Indigenous peoples in Canada. We drew from these socio-political and economic issues and interpreted the architectural envelope to voice the resiliency of Indigenous peoples. These gestures as a parallel between the common narrative of resilience that Indigenous peoples have in the face of adversity, as they continually press-on through past genocide and present dehumanization. Resilience is meant to be felt through the physical, emotional, environmental and intellectual realms through each art piece and the environment that shelters it.”

2. “Manoomin (The Good Seed): How the Erasure of One Plant Represents a Relentless History of Deprivation” by Claire Leverton (LAN1012)

“Across Southern Ontario, wild rice or manoomin once grew in abundance. For the Anishinaabeg people every transition of this plant’s life is intrinsic to cultural grounding and sovereignty. As with the principles of the Honourable Harvest, manoomin harvesting revolves around respect and care for the plant. In the gentle nature that the plant is seeded and harvested, as well as the resources that are left to allow the plant to regain its strength. We have taken sacred gifts from All our Relations and created commodities out of them. As a society we continue to accept the loss of Indigenous peoples’ land- and human rights, including current-day boil water advisories and lack of clean drinking water on reserves. We must remember that Manoomin is only one plant that is deeply entwined with regional landscape management cultural and political systems. Yet its history encompasses century-old and ongoing land dispossession. What more could we find by digging into the histories of just one more plant?”

3. “Hug” by Abida Rahman and Sammi Ku (ARC1012)

“Inspired by Michael Belmore’s Somewhere Between the Two States of Matter, this project studies the natural formation of river rocks on how time and water places and shapes them and how they intersect with one another. The tension in the voids between the rocks is the area of interest in this project. Thus, the gallery space in our project is the ‘in-betweenness’ between two rock forms as they hug and embrace. Inherently, collecting and displaying artifacts is a very colonial ideology. This design starts to depart from the colonial discourse, through the close study of the material culture and material treatment of the Anishinaabe peoples.”

4. Inspired by Walking with Our Sisters by Christi Belcourt

Marly Ibrahim, Christopher Law and Anvi Nagpal (ARC1012)

“Walking with Our Sisters by Christi Belcourt is an installation art piece that commemorates missing and murdered Indigenous women and children. The sacred circle, which the vamps are organized around, symbolizes infinity, so that the women may never be forgotten, creating an ongoing memorial. With this in mind, our design aims to further amplify this experience through a procession walkway, spanning 10 meters, leading into a circular light frame timber structure that further opens up to a conical oculus. Since the opening of the sacred circle traditionally faces east, where the sun rises, the oculus angles towards east as well.”

5. Inspired by Ursula Johnson’s Mi’kwite’tmn (Do You Remember)

Denise Akman and Noel Sampson (ARC1012)

“Ursula Johnson’s Mi’kwite’tmn (Do You Remember) is a work of performance art. The work sees the shaving of ash wood, a wood that is both sacred and culturally significant to the Mi’kmaq First Nations. In her performance, the wood is stripped down into thin ribbons traditionally used within Mi’kmaq basket weaving. Through this, she challenges the prevalent Western-centric approach of archiving Indigenous cultural traditions still active within contemporary practice and placing them within anthropological sections of Western museums and galleries. Our design seeks to elevate both Ursula herself and the tension she works to expose. Populating and inhabiting the rings of a silo-like form gives relevance to the feat of her performance and a lasting space for her to practice and share her work.”

6. “Seed Keeping and Knowledge Keeping: Storying Seeds through Past, Present and Future Practices” by Georgia Posno and Ram Espino (LAN1012)

“Many heirloom seeds show their story in their physical form. The wild goose bean is cream coloured with black speckles, the eye of the bean has an orange hue, and if you hold this seed in your hand, you may think that you are reading a book. Seed keepers across Turtle Island have preserved the physical forms of seeds and thus, the stories and sovereignty embedded into them. As we began our project, we knew we wanted to evoke a sense of community and cultural resurgence in our research. So, we became very interested in knowing who the caretakers of the seeds are, and how we can make visible their teachings.”