25.06.20 - Adrian Phiffer releases Strange Primitivism, a book of essays on architecture and teaching

Adrian Phiffer, an assistant professor at the Daniels Faculty, didn't come up with the name for his newly released book, Strange Primitivism, entirely on his own.

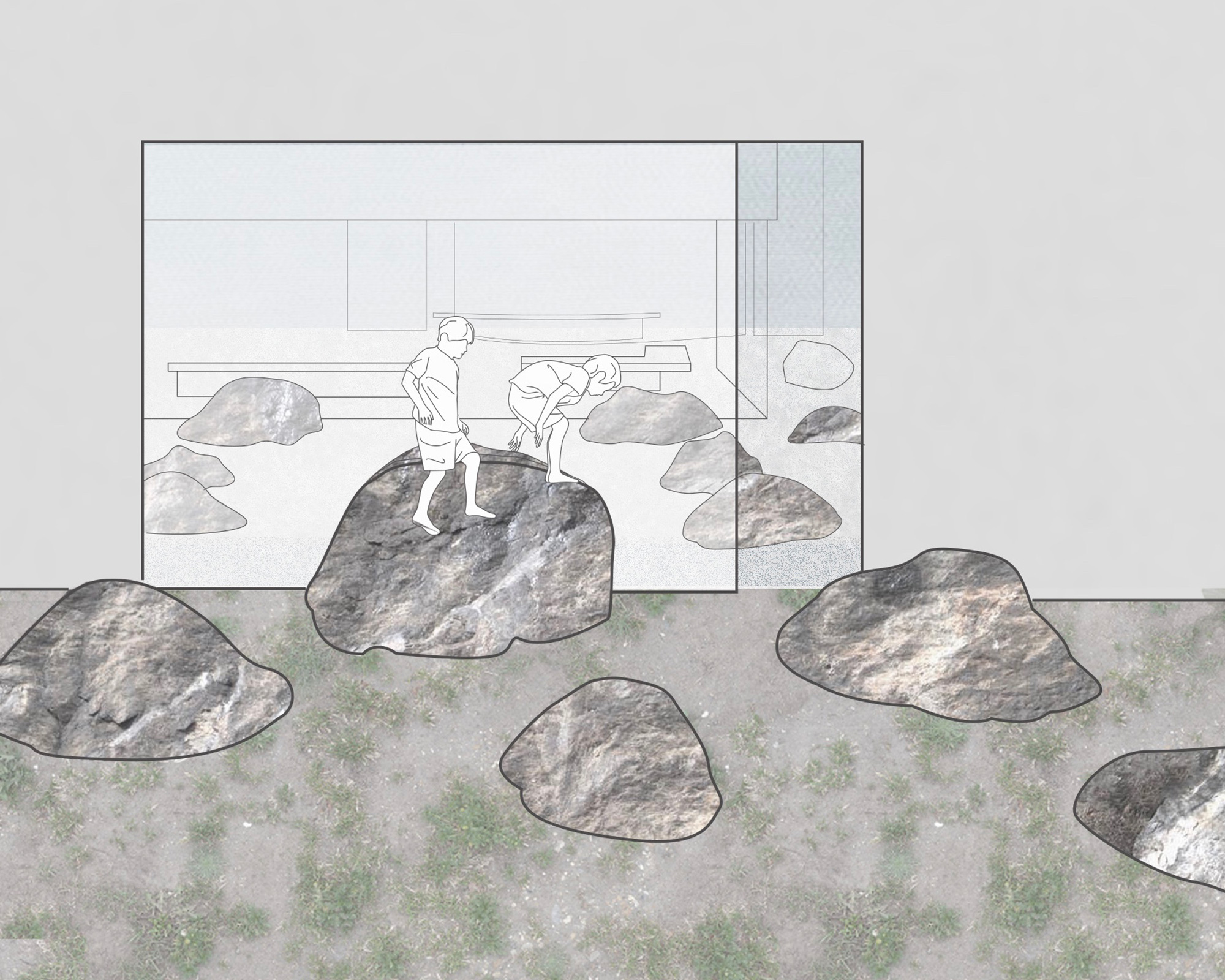

"'Strange primitivism' is a characterization that I've heard friends using when they speak about my design work. It's not my own invention," he says. "The reason I'm embracing this characterization is that I do think my designs aim towards a sense of primitivism — meaning, a sense of legibility and honesty in the way that form, materials, and program are being manipulated."

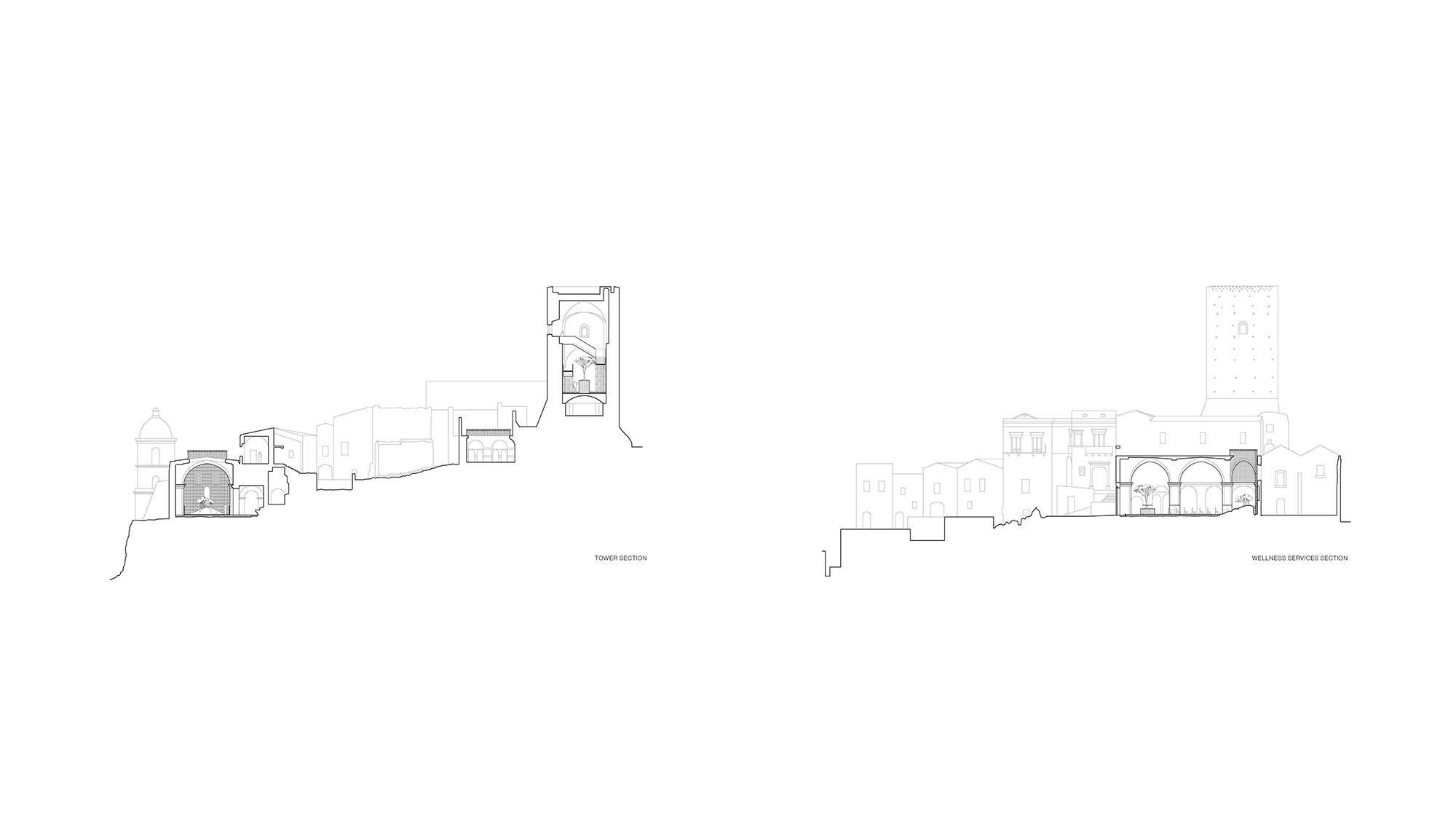

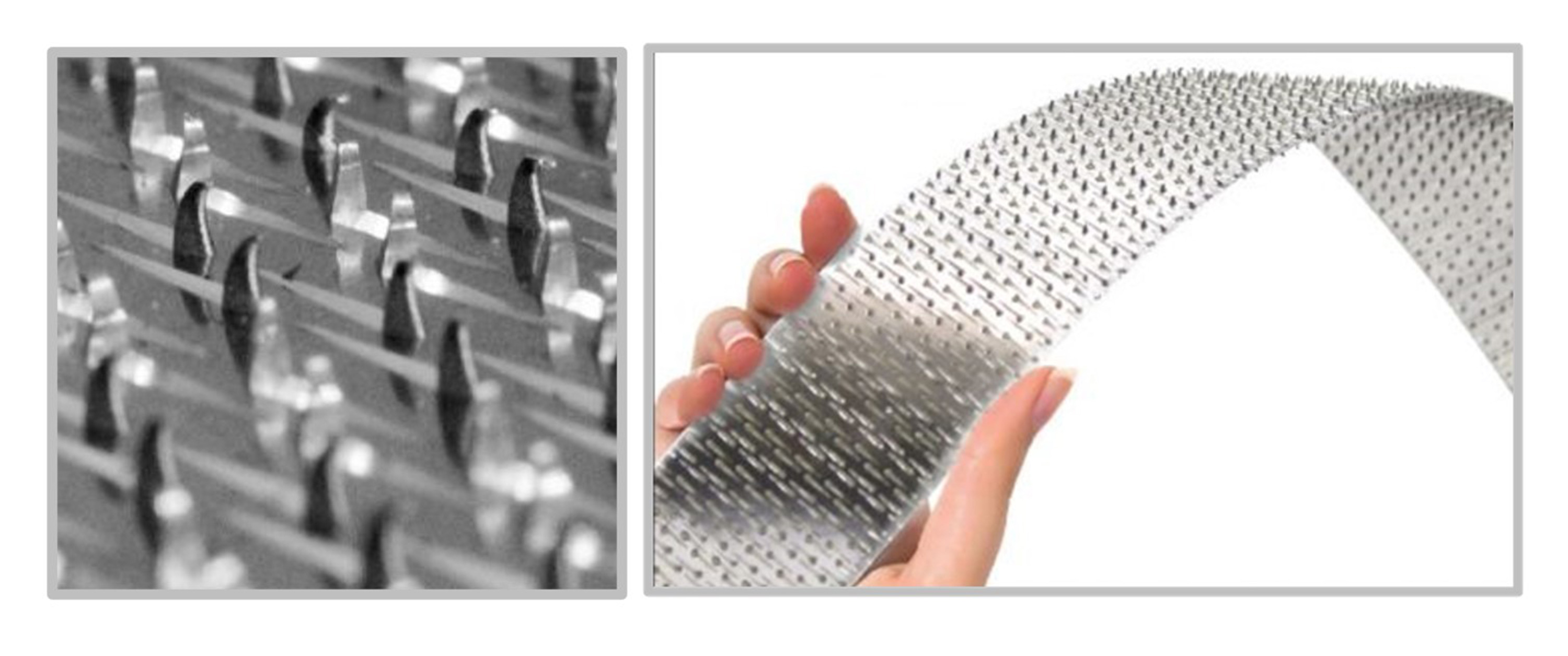

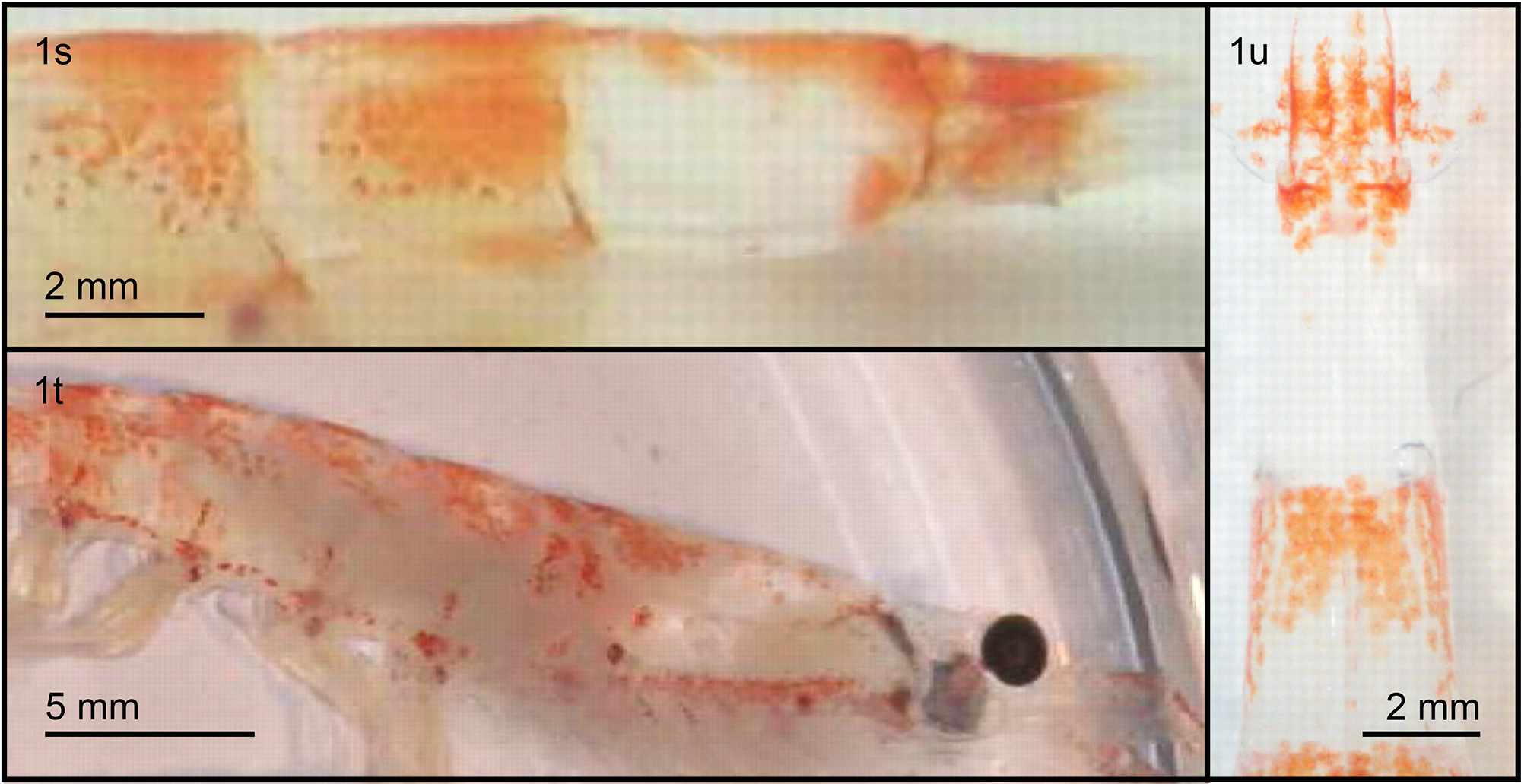

The book, a collection of 35 essays about Phiffer's architectural design practice and his experiences teaching design students at the Daniels Faculty, went on sale yesterday. It includes autobiographical notes, brief treatises on architectural theory, and thoughts on life and design in Toronto.

The volume was published by The Architectural Observer, a small publishing house run by Daniels Faculty lecturer Hans Ibelings.

In his writing, Phiffer has attempted to replicate some of the forthrightness that he strives for in his architectural practice. "Overall," he says, "the book is characterized by a sense of honesty that maybe is typical for someone who has grown up in Eastern Europe." (Phiffer is from Romania.)

"My ambition was to unearth parts of the process of working in the architectural realm that sometimes are not fully revealed, because designers would feel uncomfortable revealing them."

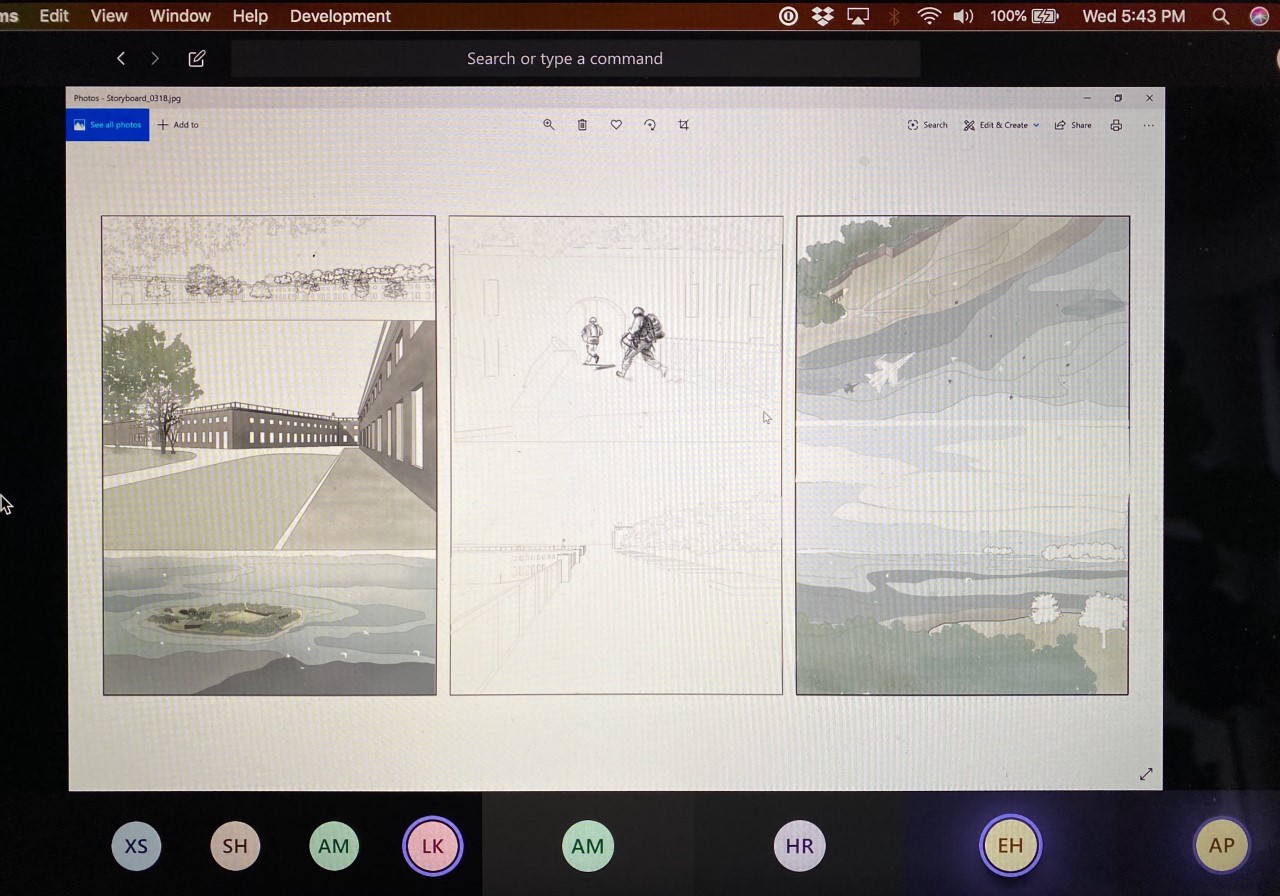

The book's intentionally fragmented layout and its four different covers (which Phiffer says are a way to "engage with readers in a visual dialogue about having, or not having, an image") were created by Haller Brun, a Dutch designer. The pages are filled with images of Phiffer's projects, as well as his students' projects.

Strange Primitivism's cover price is $37.50, and it's now available on Amazon.