21.04.22 - Eco-warriors: On Earth Day, three leading landscape architects discuss their discipline’s thrilling potential (and responsibilities) in a fast-changing world

More than ever today, landscape architecture and design have become key aspects of planning and building, which can no longer afford to ignore the natural world. This wasn’t always the case. For Earth Day, three University of Toronto graduates with diverse experience in the field convened to take stock of how far the discipline has come – and how far it can go. Below, the unabashed ecology advocates Doris Chee, Eha Naylor and Shelley Long share their thoughts on the changing perceptions and approaches of their profession, how landscape architects can lead the way in addressing issues such as climate change, and a few of the game-changing projects they themselves have worked on.

Tell us a little bit about yourselves.

Doris Chee: I graduated from University of Toronto in 1984. I worked at various private and public offices for most of my career, until I landed at Hydro One, which is where I have been for the last 14 years.

Doris Chee was born in Hong Kong and immigrated to Canada when she was nine years old. (Photo provided by Chee)

I was always passionate about landscape architecture. I volunteered with the Ontario Association of Landscape Architects (OALA) newsletter when I became a member, helped mentor junior landscape architects, and represented the association at various meetings and committees. I’m still doing that. I worked my way up, so to speak, to the position of OALA president from 2016 to 2018. I also became involved with the Governing Council of the University of Toronto.

Eha Naylor: I studied at U of T, at what was then known as the Faculty of Architecture and Landscape. I graduated in 1980, and was lucky enough to have some rather good female mentors along the way.

Eha Naylor grew up in Toronto. Her parents immigrated to Canada from Estonia in 1940. (Photo provided by Naylor)

I chose landscape architecture because it was a field where I could combine art and science – I had an interest and natural affinity for both, particularly natural science. It was really exciting when I found a program and a profession where I thought I could be happy working for the rest of my life. And I’ve been working there for 40 years now.

I’m now a partner emeritus, which means I’m retiring soon. So that’s a good thing, but I don’t think I’ll ever give up being part of the landscape architecture profession and advocating for it. I think it’s just the next logical step. I met Doris when she was OALA president, and I was chair of the practice legislation committee at the association. And I’m also currently the president of the Landscape Architecture Canada Foundation, which is the foundation that provides scholarships and grants for research and scholarships to students.

Shelley Long: In my high school years, I was quite the environmental activist: started a green club at my high school (secured lots of funding for it) and participated in eco art contests. When I went to university, I was looking again for a profession where I could blend art and science. I think that’s really common for a lot of people who are in landscape architecture.

Shelley Long was born and raised in Calgary. Her father initially immigrated to Canada from south China to do his PhD, and ended up bringing his wife with him as well. (Photo provided by Long)

In terms of how I ended up where I am today, I graduated from U of T in 2015, then worked for five years in Vancouver in both private practice and as adjunct professor at the University of British Columbia, which I found a very rewarding experience. I love teaching, and I love being involved in both aspects of practice and academia.

Four years ago, I moved to Rotterdam in the Netherlands, to join the team at West 8 Urban Design and Landscape Architecture. I had read [founder] Adriaan Geuze’s book when I was a student in Vancouver and actually attended his lecture when I was studying at the Daniels Faculty. I really wanted to work with him, so I guess I made that dream come true.

I’m a registered landscape architect in Ontario and B.C. and I do most of my work in Toronto, but also in the U.K. I don’t teach anymore because I don’t have time for that with this job.

Eha, you were recently appointed to the U of T’s governing council. Congratulations!

Naylor: Yes, thank you. It was announced in February. The council is essentially the University’s board of directors, and I’m one of the alumni governors. My role is, I believe, to champion the interests of the alumni, and to be part of the decision making for the University and its implications for alumni.

It doesn’t start until July, so I’m in training mode at the moment. There’s a learning curve for it. I have to give thanks to Doris, because she gave me a little push; she was very gentle about it, but she said you should do this. I’m looking forward to it. It is part of that transition from active practice to personal [endeavours].

How would you define that spectrum between active practice and personal pursuits?

Naylor: It’s the ability to have time to give back. I think I’ve been lucky in my professional life. I started in private practice and remained in private practice, and was part of a smaller, very progressive firm, led by Michael Hough and Jim Stansbury, in the 1980s. I ultimately became president of that firm. In 2009, we joined Dillon Consulting, a larger, multidisciplinary engineering firm.

These days, climate change, sustainability and protecting natural systems are paramount aspects of designing landscapes. How do they intersect with your work? And why are they important to you?

Long: As landscape architects, our role is to help connect people with natural systems. For my master’s studies, I had to choose between architecture or landscape architecture. I chose landscape architecture because it dealt with open systems and not closed ones. Landscapes only become better with time, whereas buildings start to fall apart the moment they’re complete. I thought, instead of making a fixed-point contribution, why not make something that gets better and more beautiful with time.

Naylor: I agree with Shelley. I think that is fundamentally not only why we choose to be landscape architects, but also why we continue to be landscape architects. About five years into my training, when I was first hired, I was quite frustrated. Not because of the work, but just because of the state of the business in those days. There wasn’t yet this kind of acceptance or understanding of how important it was to have a big picture of the environment. Landscape was relegated to tinkering around the edges.

To stay in this profession, you have to be able to embrace and articulate the larger vision of what it does. There have been environmental catastrophes, including climate change, that have made taking care of the physical environment and natural systems more understandable and urgent, whether they’re urban systems that provide natural environments or larger ecosystems.

Chee: These issues, as Eha said, have come to the fore because of events that are happening now. But that’s how we’ve always projected our work: adapting to climate change, being more sustainable, being more diverse in our work. And whatever we do, small or big, there’s a ripple effect, a downstream effect that becomes exponential.

Looking back on your careers now, is there a paradigm shift that you see within the profession when it comes to addressing these issues?

Naylor: Absolutely. In the 1980s, the concept of large-scale ecological restoration just wasn’t accepted. For example, I think it was probably in the early eighties that Michael Hough developed the strategy for the Lower Don Lands, and it involved recreating wetlands. He worked with a geomorphologist. And the work was certainly accepted, but it wasn’t widely accepted by other professionals.

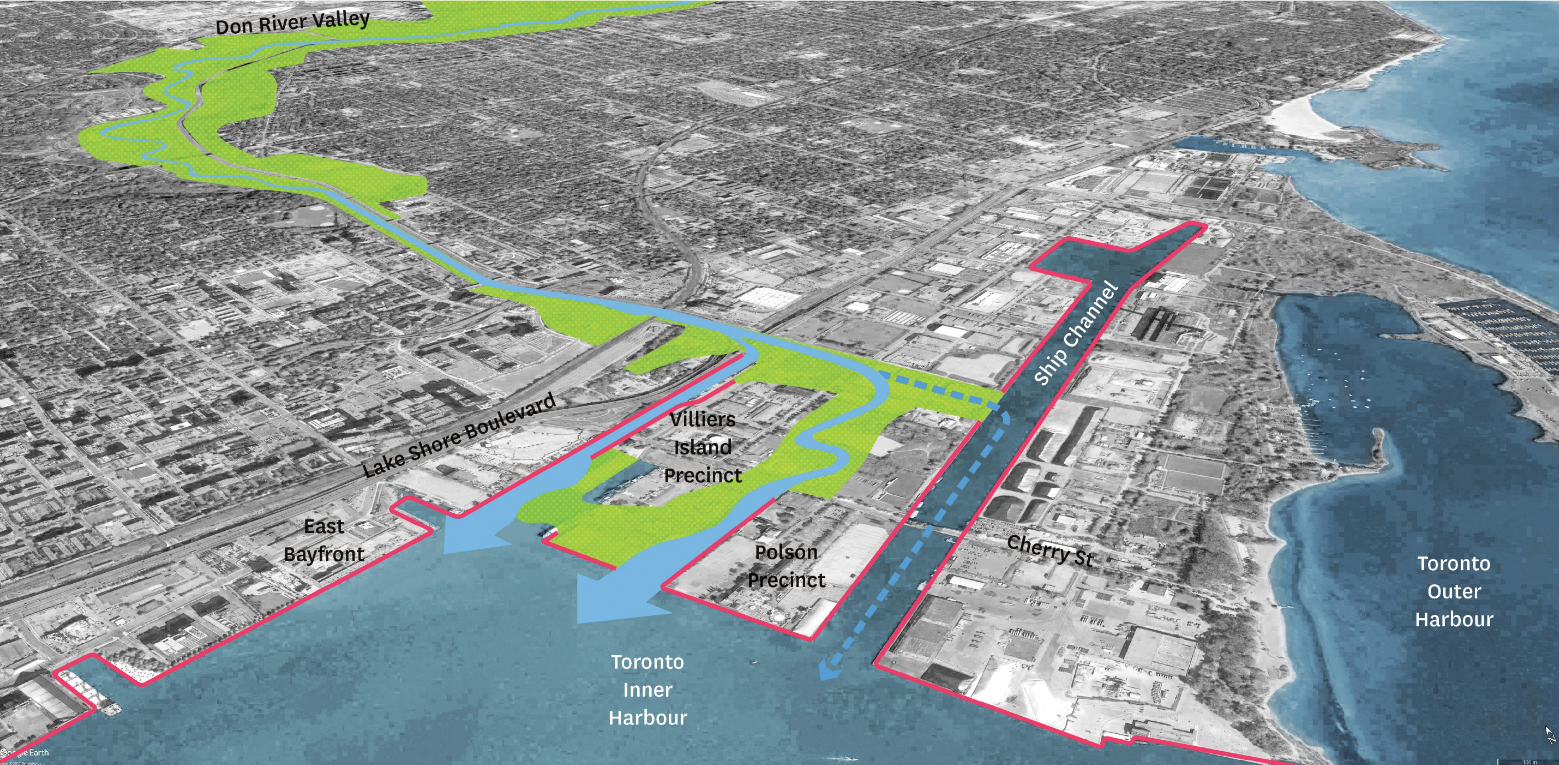

Stormwater management was still viewed as putting in a pipe; water was a nuisance to get rid of as quickly as possible. If you look at the work that’s happening now in the Port Lands, it is a huge change in thinking. The Don River [which is being renaturalized at its mouth] is becoming an enormous resource and the catalyst for a very important and high-quality renewal of the port.

That idea, I think, was initially outlandish for many and now it is mainstream thinking. But it’s probably taken 25 or 30 years for it to be accepted. I really admire the work that has been going on forever in the Netherlands. They’ve had to address these questions [of flooding and resiliency] for a long time, and have been able to explore those ideas physically.

A map from the Port Lands Flood Protection Project, showing the Don River flowing into Lake Ontario. (Illustration from slide presentation PDF)

Chee: What they’re doing in the Port Lands is ecology-based. And I go back to thinking about how it has shifted. Well, let’s look at trees, for instance. In the early days, we were choosing trees to plant for their aesthetics, not so much their ecological effects. Now, we’re planting for sustainability, for carbon capture.

Shelley, as someone who’s part of the younger generation of landscape architects, have you noticed any changes in how these issues have evolved within the profession?

Long: By the time I came into the profession, a lot of the things that Eha is characterizing as paradigm shifts were already in place, which is a good thing, I guess, in how this way of thinking has become ingrained in the profession. But I could speculate that it might also be a bad thing. We sometimes put a lot of pressure on ourselves as young professionals to say that landscape architecture is going to save the world. I don’t think it is. And I need to be realistic about that, with my peers and also with students. We need to work together across disciplines and backgrounds to solve climate change, and also convey to our clients, for instance, that landscape architects can’t and shouldn’t go at this alone.

Naylor: Climate change is a really messy problem requiring a complex methodology for resolution, and the skills of many different disciplines. Landscape architecture is one of those disciplines and frankly a very valuable one, because we understand that idea of systems-based thinking for our physical environments. I’d say very regularly, as part of the lead of the practice legislation committee, that landscape architects must have a voice at the table when these kinds of issues are being addressed. We have to weave in our expertise with those of engineering, architecture and science to be able to come up with solutions that not only make sense and are sustainable, but also benefit communities. So, I agree, it’s not something that landscape architects alone can solve.

Can you cite some of the projects that have addressed these issues through landscape architecture?

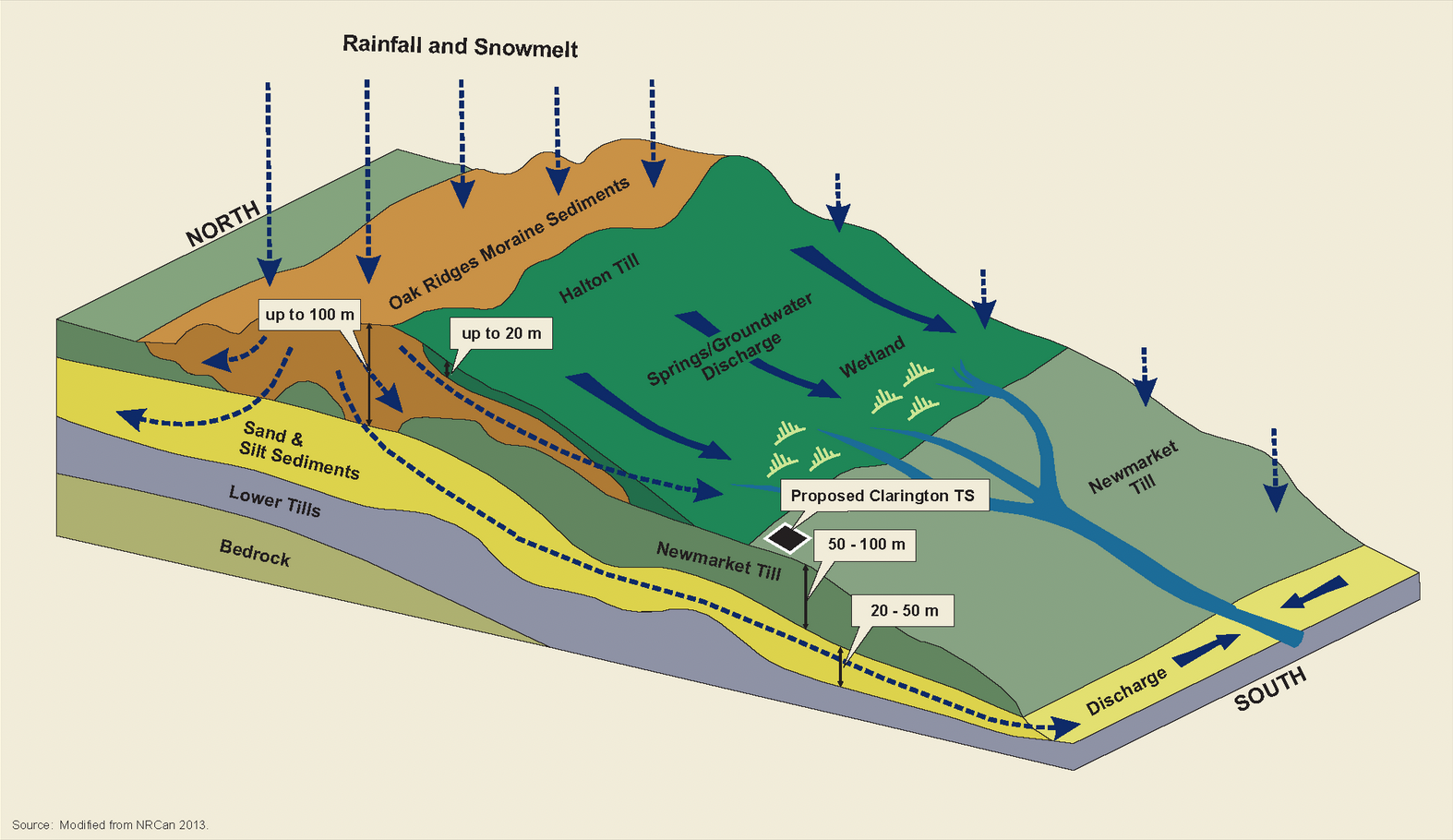

Chee: One project we just finished is the Clarington TS Project. Eha’s company, Dillon, has helped us with it. Hydro One is in the business of transmitting electricity throughout Ontario and this was one of the major transmission projects that we designed and developed over 10 years. It’s a major centre that transmits 500-kilovolt power to the eastern borders of Northern Ontario. It is very unusual for Hydro One to own a large piece of property, where we can build a major station and still have leftover land. It just so happened that this piece of land sits on moraine, has two streams running through, a little woodlot, and most of it was cultivated for agriculture.

Schematic of Oak Ridges Moraine. (Illustration from Hydro One)

Due to the number of towers that had to go into this project, as well as the station itself, we couldn’t allow the farmers to come back and use that land. We looked at the various ecosystems, and the different methods to enhance the natural system. We worked with the local conservation authority, which helped us greatly in finding the right methodologies to incorporate into this piece of property. And the last thing that we did was create a small wetland to help ease up on some of the runoffs that was happening downstream.

Long: In the Netherlands, there’s a project called the Noordward polder, where the Dutch government decided that the river needed more room to allow it to flood because of the extreme events that are happening more frequently. To address this, they broke the project into small, different regional projects, which were awarded to engineering companies. One of them was to take this old historic polder that was farmed for hundreds of years, and open it to become basically a place that the river could flood into during storms. All of the farmers there were to be moved away, in order to transform it into an ecological park.

West 8 was the sub-consultant on this project and had this idea of, let’s look at the nuances of the different flood levels when they’re happening, where they’re happening, and propose to the ministry: how about we raise the inundation dikes, raise all the lands that the farmers are on? They go away for a few years, we rebuild their houses on higher ground, and they then live within the changing landscape. We built a new series of slices and dikes, which is all very much in the language of the Dutch water system. And now what you see is that the farmers are able to stay in their homes, and you have a new type of place created, [a paragon of] what we call flood tourism. People actually go there and can see when everything is flooded except for the little rows, the little farmhouses, and the little pump stations.

People, I think, are craving that. They want to understand how the landscape works, in relation to extreme events and climate change. I think that’s a wonderful example of the systems-based thinking of landscape-led infrastructure and place-making.

If people would like to read on this further, and see some of the images, topos magazine has a great issue on it called infrastuctures. I was involved in the curation, peer review, editing and writing of a number of pieces for this issue.

Naylor: One of the projects that I spent a lot of time working on was the Windsor-Essex Parkway [now called the Rt. Hon. Herb Gray Parkway] which is the extension of the 401 Highway right through the city of Windsor, Ontario. We took the results of multiple environmental assessments conducted over the years and developed a design strategy, which essentially put the highway into a trench. We created 11 land bridges across the trench. There was, I believe, almost 100 hectares of ecological restoration of tallgrass prairie and oak savanna. It was an incredible project, because it took what would normally be and what the community thought would be a blight and turned it into an incredible ecological resource. We also had the privilege of working the local Indigenous community, the Walpole Island First Nation, and we were able to express both their culture and the project through art and signage.

Renderings of the Rt. Hon. Herb Gray Parkway project from Dillon Consulting.

The other project I’m currently working on is the long-term vision plan for Parliament Hill. The physical setting for Parliament Hill is complicated. It’s also politically complicated. The Parliament Building is perched on a hill which is the remnants of a valley that over a decade have been degraded. There’s a huge opportunity to restore the natural environment to contribute to both the cultural environment as well as the political environment. It’s a significant challenge, but if it’s solved through the right lens, it can encourage Indigenous reconciliation, and it can make the public realm on the Hill a better place. It can be a place of incredible pride for Canadians.

What advice do you have, finally, for people who are either new to landscape architecture or already in the profession on how they can prioritize and centre ecological perspectives and values in their practice?

Chee: I think of the profession of landscape architecture as a gift. And if I could be a little bit spiritual here for a moment, if we go back to the book of Genesis, the Garden of Eden was given to Adam and Eve to live in, and they were also given the task to look after it. Our profession has similarly been given the gift to be the stewards of the land. I really cherish that value, that image even, if you will. It is a gift that the result is the betterment of people, of animals, of our natural environment.

Naylor: For students in the landscape architecture program, and those who are graduating, I would encourage them to really stay focused on continuing to learn, to continue to build their skills and keep their eyes open to how the world is changing. I think we have a lot to contribute, but I also think it requires practitioners to stay in touch and be the best they can be in order to contribute meaningfully to people and to the planet.

Long: My piece of advice, on the occasion of Earth Day, is that when we talk about sustainability, we should focus on longevity as a concept. I think it’s important that we, as people in the ecological field, are able to differentiate between what’s green and what’s greenwashing. And also to explore the ideas of circularity and life cycles, what our First Nations colleagues would call the seven generation principle. I think that if you start thinking in your profession at an early stage about these concepts, it totally changes how you go about and relate to the world.