03.05.20 - Daniels undergrads expand their horizons with School of Cities capstone projects

During this past academic year, a few Daniels Faculty undergraduates were participants in the first-ever School of Cities Multidisciplinary Urban Capstone Project, a full-year design program in which students from different disciplines work together on a complex project for a government or nonprofit client. The program is a chance for students to learn firsthand about the complexities of delivering a real-world design project in an urban context.

Six Daniels students worked with students from other university departments on four different design projects for four different clients. Below, some details on two of those projects, the students who worked on them, and what they learned in the process.

(If you're a Daniels Faculty student entering your fourth year of undergraduate architecture studies and you'd like to apply to participate in next year's Multidisciplinary Urban Capstone Project program, see the School of Cities website for details. To undertake a School of Cities capstone project, students must first have applied to — and been accepted into — the Daniels Faculty undergraduate thesis program.)

Ghalia Alchibani Alnahlawi and Lucas Siemucha

The School of Cities placed Ghalia and Lucas, both architecture undergrads, in a work group with Jonathan Mo, a senior at Rotman Commerce. Their client was John Lyon, a senior city planner who acts as a liaison between the city of Toronto and public school boards.

Lyon's problem had to do with schoolyards: because of a lack of funding and limited maintenance staff, many schools around the city struggle to keep their outdoor spaces safe and pleasant for students and teachers. Some schools also have difficulty figuring out how — and to what extent — to allow people from surrounding communities to make use of school-owned outdoor spaces when class isn't in session. Ghalia, Lucas, and Jonathan were tasked with studying these problems and coming up with a suite of solutions that could be applied throughout the city.

The three students approached their task like professionals. They attended monthly meetings with Lyon and representatives from the Toronto District School Board and the Toronto Catholic District School Board. After getting a sense of the client's needs, they selected four specific schools to use as case studies. They visited those schools and conducted questionnaires with leadership figures at each one.

They discovered some unexpected obstacles. "Funding is a huge issue," Lucas says. "School boards don't have enough money to put new equipment in the schoolyards or repave them. Some schools actually do get some funding from parent councils, whereas there are high-needs schools that don't gain enough support."

Through research and consultation, the students refined their problem down to a series of key priorities that needed to be addressed at each school: safety, cost efficiency, sustainability, community engagement, student learning, and opportunities for public-private partnerships.

Next, the students spent some time thinking about design solutions that could help schools achieve those priorities in their outdoor spaces. They developed a guidebook of ideas — a sort of toolbox full of design solutions that they could apply as necessary, depending on the needs of a specific school.

With Jonathan focusing on funding, financing, and third-party outreach, Ghalia and Lucas set about tackling the design component of the project. For each of their four case-study schools, they developed a detailed design proposal.

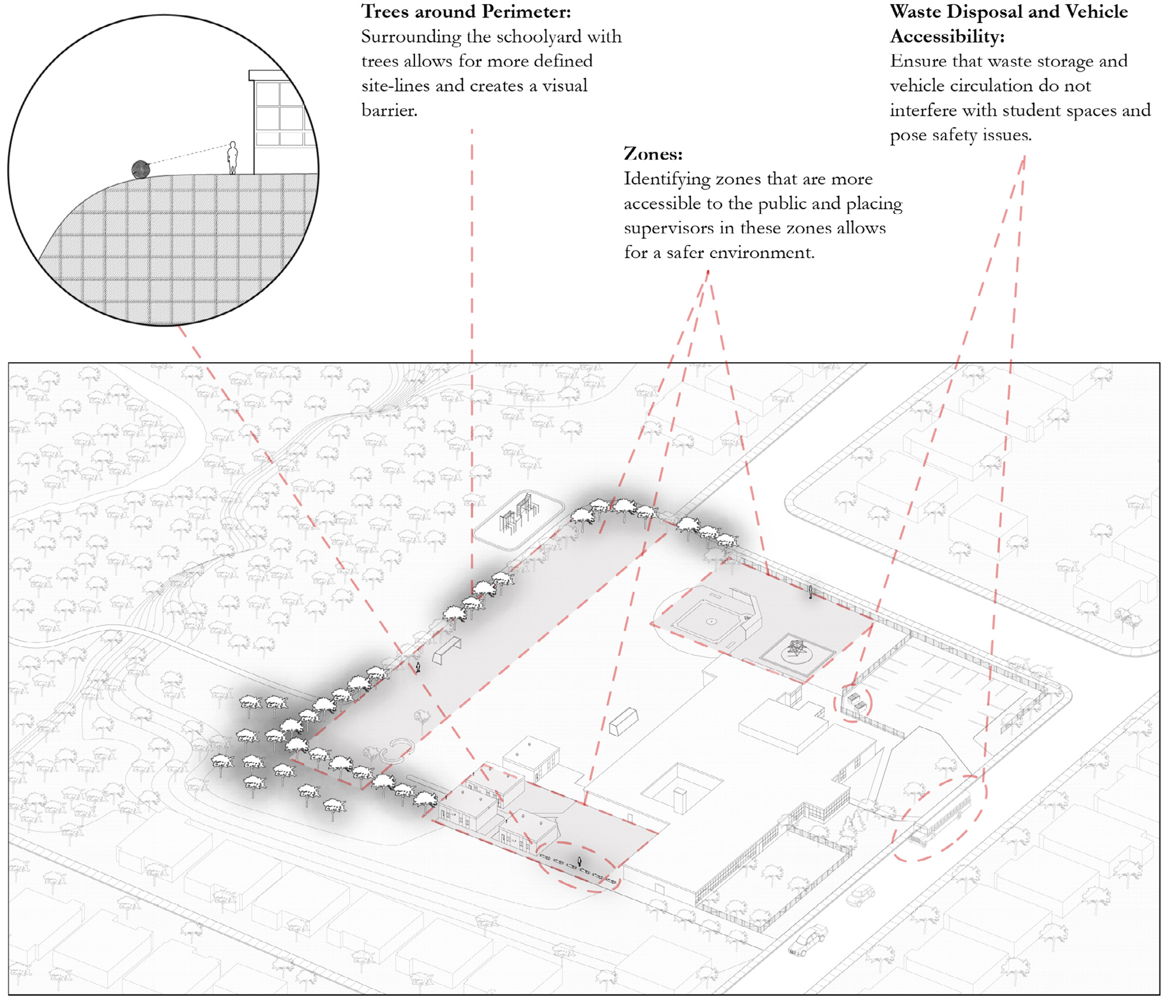

A site plan, showing trees used as a natural perimeter at Chalkfarm Public School.

One of the group's case studies was Chalkfarm Public School, in North York. The school's administration expressed concern about the safety of the schoolyard, which is open to the surrounding neighbourhood. Ghalia and Lucas suggested using rows of trees to create a natural perimeter around the yard, which would add some privacy without the cost or unsightliness of a fence. The trees, they suggested, could be sourced at low cost from a partner organization, like the Highway of Heroes Tree Campaign.

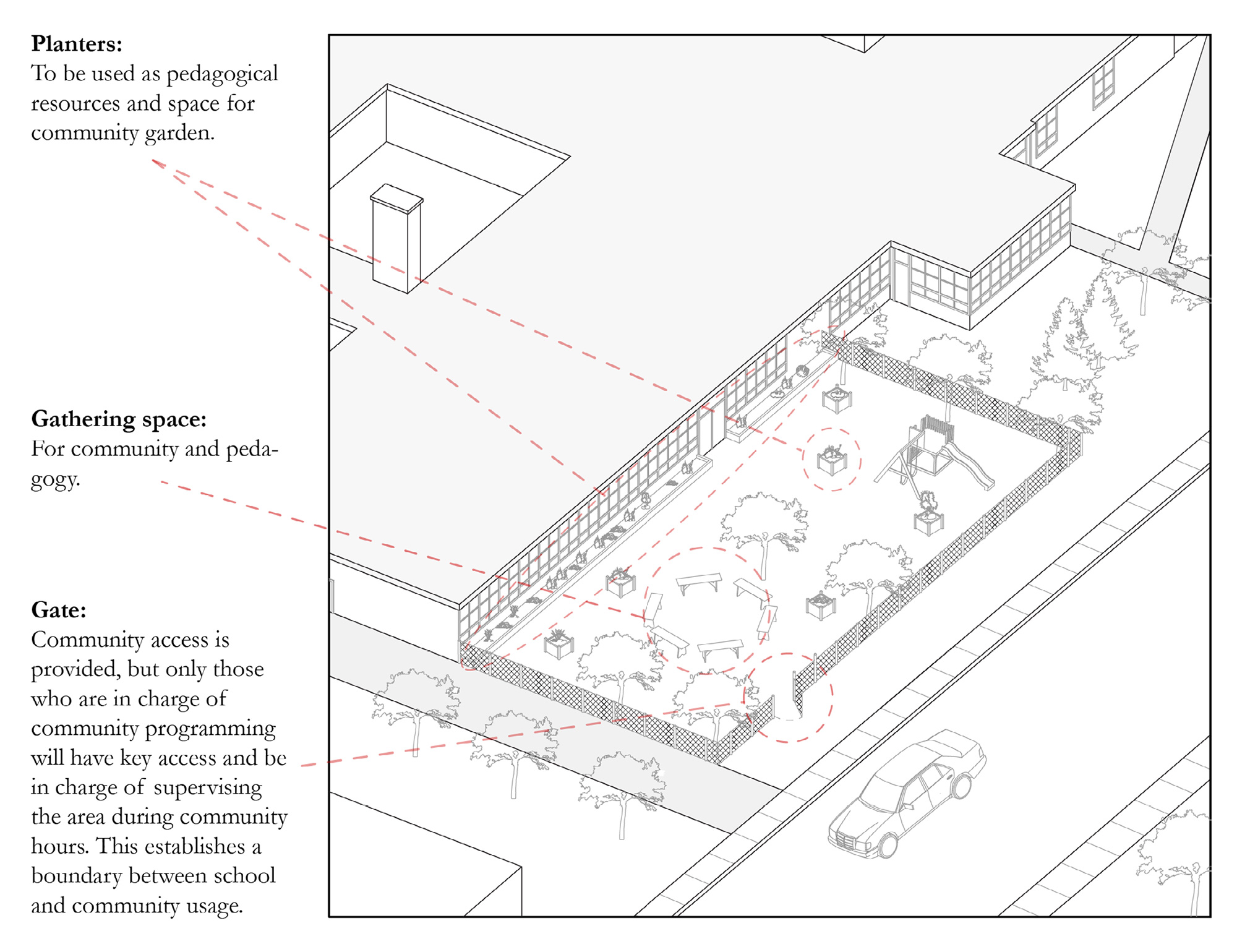

In order to enhance community engagement at the school, Ghalia and Lucas suggested adding planters to an existing outdoor play area. The planters would become the basis of a community garden, which could be used as a pedagogical resource. A few trusted members of the public would be able to volunteer in the garden, and a lockable gate would keep strangers away, ensuring the safety of young students.

Ghalia and Lucas's combined play area/community garden.

They delivered their final design guidelines and case studies to their client at the end of the academic year. Now it will be up to the city government and the school boards to decide how to implement the students' recommendations. Regardless of whether their designs are implemented, Ghalia and Lucas say the learning experience was worthwhile.

"This project was eye-opening," Ghalia says. "I learned a lot about urban design and landscape, which are very new to me. And it was really interesting to work on something that could potentially make a change for people."

Sara Ghorban Pour and Evan Guan

Sara and Evan, both architecture undergrads, teamed up with Sarika Navanathan, a student at the Rotman School of Management, to take on an urban design challenge on a (much) smaller scale.

Their client was the city of Toronto's urban planning division. For the past 30 years, the urban planning division has maintained a scale model of Toronto's downtown core. The model is large — it's 1:1250 scale — and it's on permanent display in the rotunda of Toronto's city hall, where it's frequently seen by tourists and dignitaries.

Maintaining the display has been a problem for the city's urban planners. The model is composed of thousands of handmade miniature buildings. Because the process of creating and adding new miniatures is so laborious, and because the city has transitioned to using digital models for most planning purposes, the scale model has rarely been updated over the past three decades, even as Toronto has added countless new tall towers and experienced considerable change to its neighbourhoods and street grid. The scale model is now badly out of date.

The scale model, in the city hall rotunda.

Sara, Evan, and Sarika were given the job of figuring out a way to revive the scale model without spending an inordinate amount of taxpayer dollars. The client was also interested in developing a plan to engage outside organizations in the model's upkeep.

While Sarika worked on the community partnership aspect of the project, Sara and Evan set about figuring out how to physically upgrade the model and bring it up to date. It soon occurred to them that model-making technology has progressed considerably in the three decades since the scale model was originally built. They decided that their design solution would take advantage of modern 3D printing.

Every 3D-printed model starts as a digital file — a 3D computer object that the 3D printer replicates in some kind of physical material, like plastic or starch. Sara and Evan needed to figure out a way of gathering those digital files for hundreds of new buildings that had sprouted in downtown Toronto in the years since the scale model last received a comprehensive update.

They found a solution in the city of Toronto's "open data" portal, a website where ordinary citizens can download large sets of municipal data, like building permit records and 311 logs.

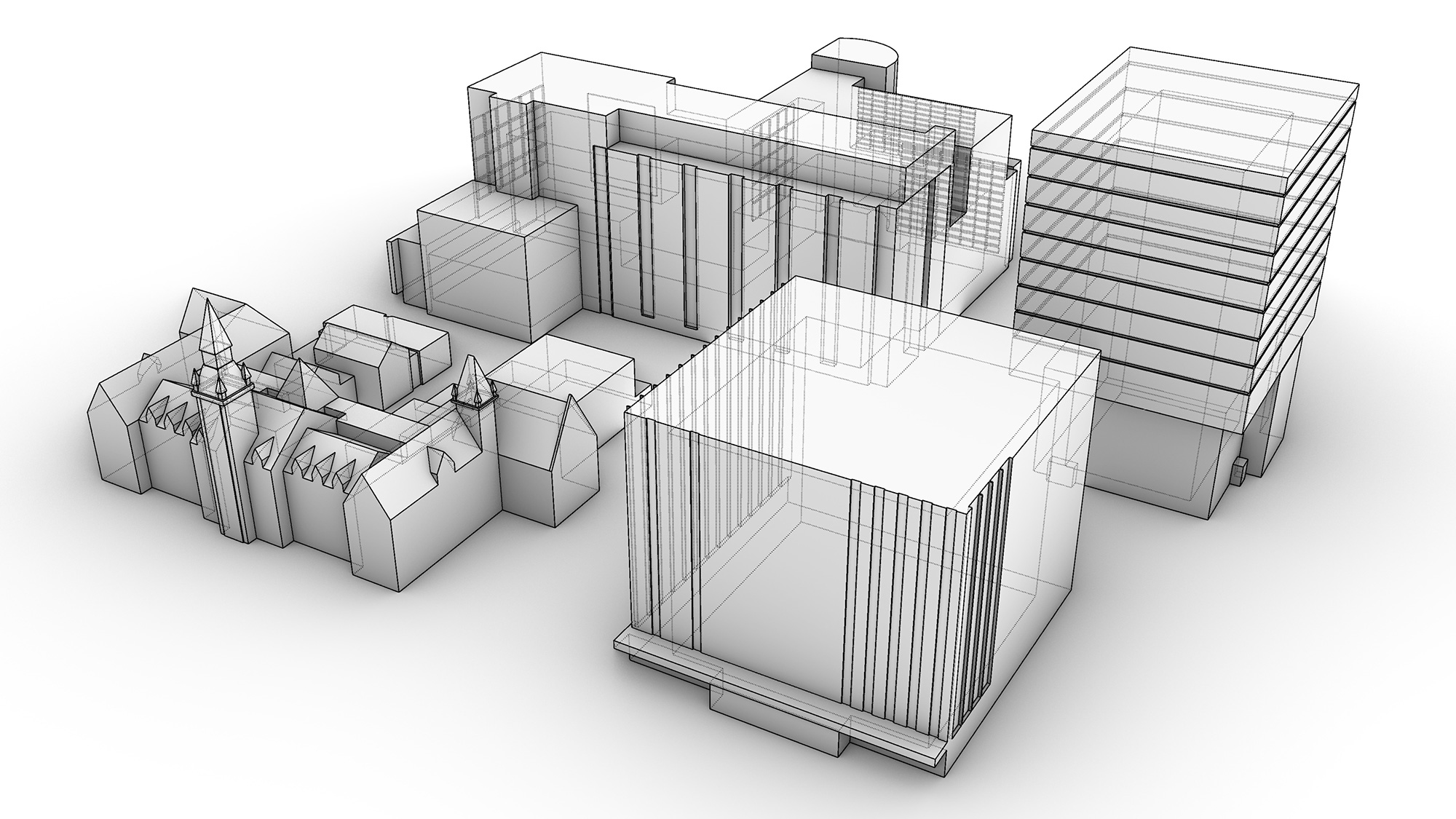

Among the open data provided by the city is a vast repository of so-called "3D massing" files — digital 3D models of city buildings. The files are accurate, up-to-date representations of the shapes of the city's newer structures — but they're not ideal for 3D printing. They have a number of technical formatting inconsistencies that would interfere with a normal printing process — and, to complicate matters even further, they're solid masses. (The cost and duration of a 3D printing process is determined by the amount of material to be printed, so it's cheaper and faster to print a hollow object.) Sara and Evan devised a process for taking the massing files, cleaning them up, hollowing them out, and resizing them to the proper scale.

Massing models.

Their next step was figuring out who, exactly, would be doing all this 3D printing. The city doesn't have the resources — but, the students realized, the Daniels Faculty does. The Daniels Bulding's Digital Fabrication Labratory has 3D printers capable of extruding durable ABS plastic, an ideal material for long-lasting architectural models.

The group's final proposal was a partnership between the city's urban planning division and the Daniels Faculty, in which architecture students would earn course credit for using the Faculty's 3D printers to help update the scale model. (The city and the Daniels Faculty have not yet responded to this proposal.)

For Sara and Evan, the project was a welcome opportunity to expand their horizons.

"It was less creative than what we usually do at Daniels," Sara says, "but it was actually more work, because you have to research a lot more, and you have to convince your client. It was a great opportunity for us to experience this kind of work."

"Normally at Daniels we focus on one building, our own design," Evan says. "This time we were working with digital massing data the size of the entire city. It was a breath of fresh air."