20.02.19 - Q & A: Simon Rabyniuk on drones in the city

On Saturday, February 23, the Daniels Faculty is hosting the Dronesphere Colloquium, a day-long event that will delve into the use of drones in cities. The Colloquium has been organized by third year graduate student Simon Rabyniuk, whose research on aerial robotics will inform his final Master of Architecture thesis. Undergraduate student Tina Siassi spoke to Rabyniuk about the relationship between architecture and drones, the regulation of low-altitude urban airspace, and how drones may affect our experience of the city.

What prompted your interest in drones in cities?

Last year, I participated in Associate Professor Mason White’s research studio, “Velocities,” which looked at different forms of land, water, and air transportation and mapped the spatial by-products of each. Through this course, I researched the history of drones and some of the aspirations for their future use. While drones are not new, their presence in cities outside of conflict zones is, and, at present, low-altitude airspace is largely uncontrolled except in the vicinity of airports. This led to a curiosity about the intersection of drones and cities, and how drones might impact patterns of movement and lead to the need for new forms of infrastructure.

How are drones currently regulated?

No city has really integrated drones into its airspace yet. Within Toronto they are explicitly regulated based on setbacks required from buildings, cars, and people. You have to be a certain distance away from airports, and there are limits on where you are permitted to launch from. Low-altitude airspace regulations are interesting to track as they are changing quite quickly. In the Canadian context a new set of regulations will take effect June 1.

What kinds of things do new regulations around the use of drones need to consider?

National aviation regulators are concerned with safety, but it is a limited idea of safety. It seeks to ensure safe operation but ignores a broader set of issues related to use and privacy. Part of my research has focused on two pilot projects testing the integration of drones in the United States. These pilots are occurring in 17 different cities. In each context, quite complex public-private partnerships are researching and testing approaches to the integration of drones. Ciara Bracken-Roche from the University of Ottawa notes how this method of working tends to make future regulations reflect a very narrow range of interests. Issues such as ecology and the aesthetic experience of the city need to be considered as well. Orit Halpern, Jesse LeCavalier, Nerea Calvillo, and Wolfgang Pietsch have a useful article called Test Bed Urbanism, which is really helpful in broadly thinking through the nature of these partnerships for introducing new forms if information and communication technology, for which the drone is but one example, to cities.

You were able to further your research on drones in cities this past summer thanks to funding from the Howarth-Wright Fellowship. How did the opportunity to travel inform your research?

The Howarth-Wright Fellowship afforded me a great deal of time for dedicated study and to engage with materials and sites that wouldn’t have been otherwise available. I was able to attend two conferences: the Military Landscape symposium at Dumbarton Oaks Research Library in Washington and the AutoSens conference in Detroit. In August, I spent about ten days at the Avery Library, which is home to Frank Lloyd Wright’s archive. This allowed me to expand the historical frame that I was looking at this with.

The archival work was great to see in person. From very early on, it seemed that Frank Lloyd Wright imagined how communication technology, such as radio or the telephone, and vehicles such as cars, planes, helicopters, and taxis could enable a decentralized urbanism.

One thing I learned from a series of interviews I did is that we have a very narrow conception of what a drone is. We often think of it as the four-propeller quadcopter. But the form of drones enables different uses and scales of action. In this sense, understanding the geography of the drone needs to account for planetary, regional, urban, and district scale relationships. Currently there is a prototype for a drone that can carry 500 pounds 20 miles. From an architectural perspective, perhaps the device itself isn’t that important, but the geographies that it produces are. This is a very logistical example, suggesting different type of supply chain, but it invites starting to think about the relationship of the drone to the city in a different way.

What questions do you hope to explore at the Dronesphere colloquium on February 23?

As this is an emerging topic, the colloquium is taking a broad focus. The day opens with a history of airspace, and concludes with a film-based performance lecture exploring possible futures of the drone. In-between are three panels bringing together landscape/architects, artists, engineers and humanities scholars which will address early stage proposals for the use of drones by designers, the current use of military drones in domestic airspace, and the role of interdisciplinary collaboration in designers working with drones. This multi-disciplinary group of speakers will provide critique, examine histories, and delve into the nuts and bolts of drone use — but the presentations and discussions will certainly invite other possibilities.

What questions are you exploring as part of your Master of Architecture thesis?

I’m interested in understanding the conditions that might produce a more diverse aerial ecology. For example, how could an urban aviary reserve that privileges the movement of birds affect the zoning of airspace? How might property relations change if the entire city becomes and airport, if every rooftop becomes operationalized in some way for drone use? I’m curious about how we might engage with this emergent technology and its possibilities.

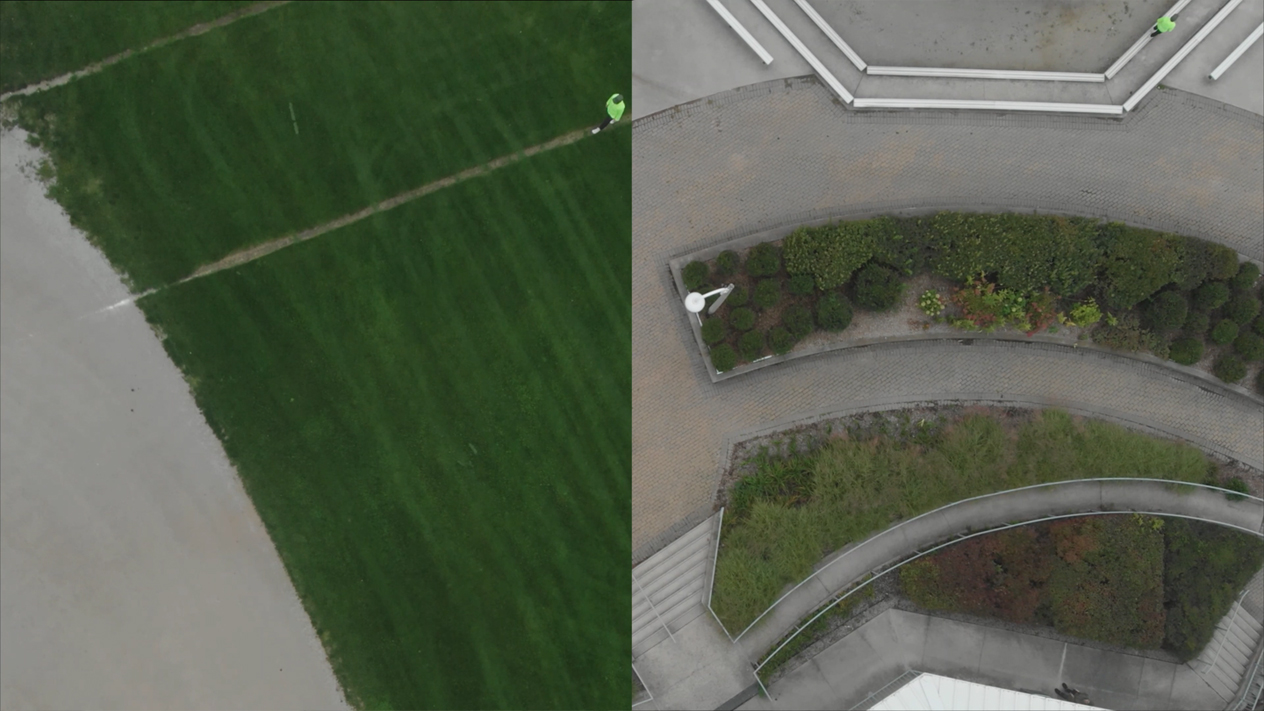

Images, above: stills from the dance film "landforms" (2018) made by Simon Rabyniuk with choreographer Cara Spooner

Are you a drone pilot yourself?

Last summer, in addition to conducting interviews, visiting different sites, and digging into the archives, I bought a drone. This allowed me to engage in a form of practice-based research that forced me to figure out what current airspace regulations meant for me as a hobbyist. It made me more attentive to the airspace above me. I started seeing the places I was walking through in a different way. I thought about what I might see if I launched a drone and took in that aerial view. Flying a drone changed my relationship with my surroundings.

Will you be continuing this research after you present your final thesis? Where do you hope to go from here?

In June I will be attending a conference to share a paper I’m working on it with a friend who is doing graduate work in law at the University of Saskatoon. The paper’s working title is “Archaeology of future airspace.” Archeology in this context refers to the history of property law as it intersects with air rights in the city. It’s an interesting topic, and there’s a lot of ways to keep working with it.

The Dronesphere Colloquium is free and open to all. Click here to register for a free ticket.

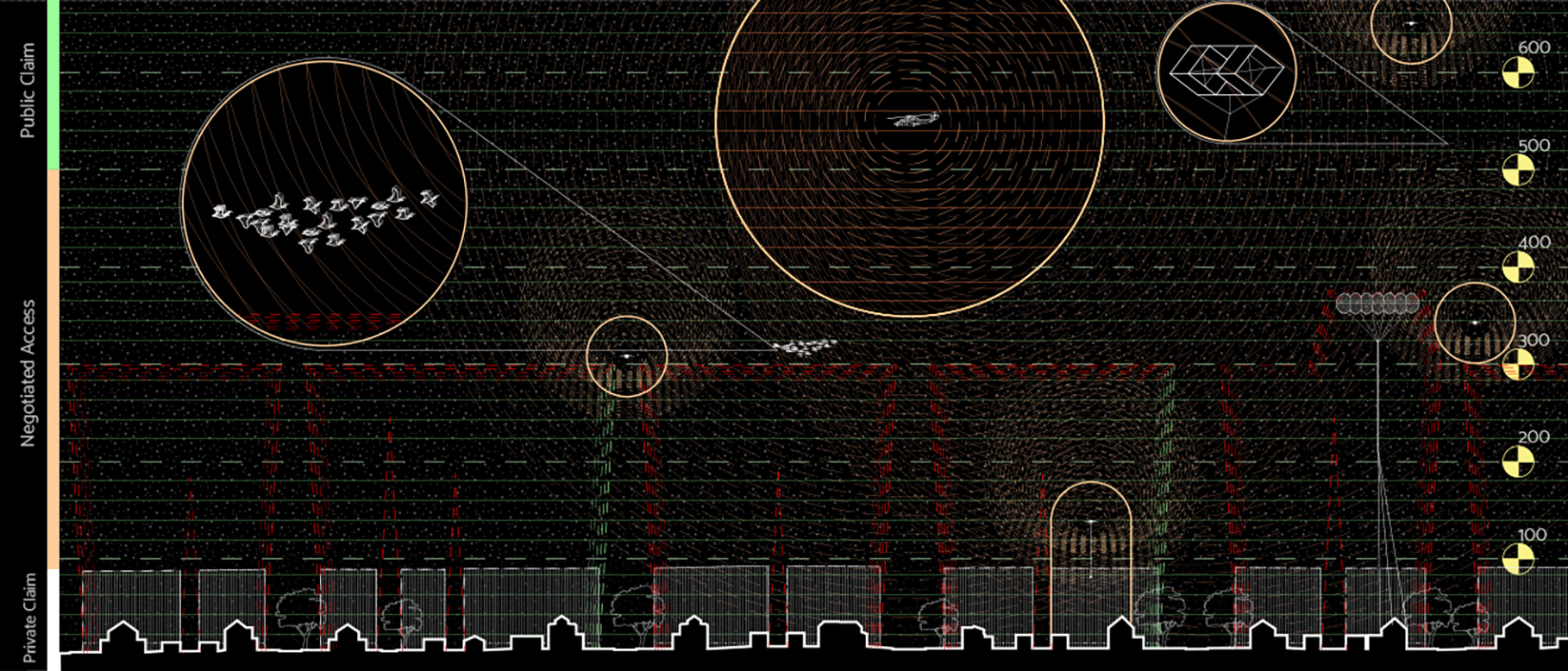

Image, top: by Simon Rabyniuk, part of a section drawing created for a pamphlet (in progress) titled Dronesphere: Roofscapes