26.05.21 - Visit this year's MVS Studio Program Graduating Exhibition online

Every year, graduating students in the Daniels Faculty's Master of Visual Studies program's studio stream work together on a final exhibition, for which each student creates an original art project. This year, with COVID restrictions making it impossible for the public to visit art galleries, the exhibition has moved online.

Four graduating studio students — Matt Nish-Lapidus, Oscar Alfonso, Sophia Oppel, and Simon Fuh — contributed work to this year's MVS Studio Program Graduating Exhibition. With the exception of Oscar's project, which didn't require physical space, all the works were temporarily installed in the Daniels Building. They were documented by a photographer before being taken down.

All those photos and videos are now on public display on the exhibition's website, visualstudies.net. There will be an online exhibition reception on May 27, starting at 5 p.m. For details, visit the exhibition's event page.

Read on for some information on the four student projects. Or visit the virtual exhibition by clicking the link below.

Take me to the virtual exhibition

Matt Nish-Lapidus

Matt's project, titled A Path, is the embodiment of his thinking about the relationships between computers, language, and mysticism. "The Kabbalah, specifically the kind of language mysticism that comes from it, was part of my research and was a big inspiration for where this work went," he says. "What I was trying to explore with these pieces was a way of thinking about computers — specifically their relationship to language, and language as a kind of poetic act of creation."

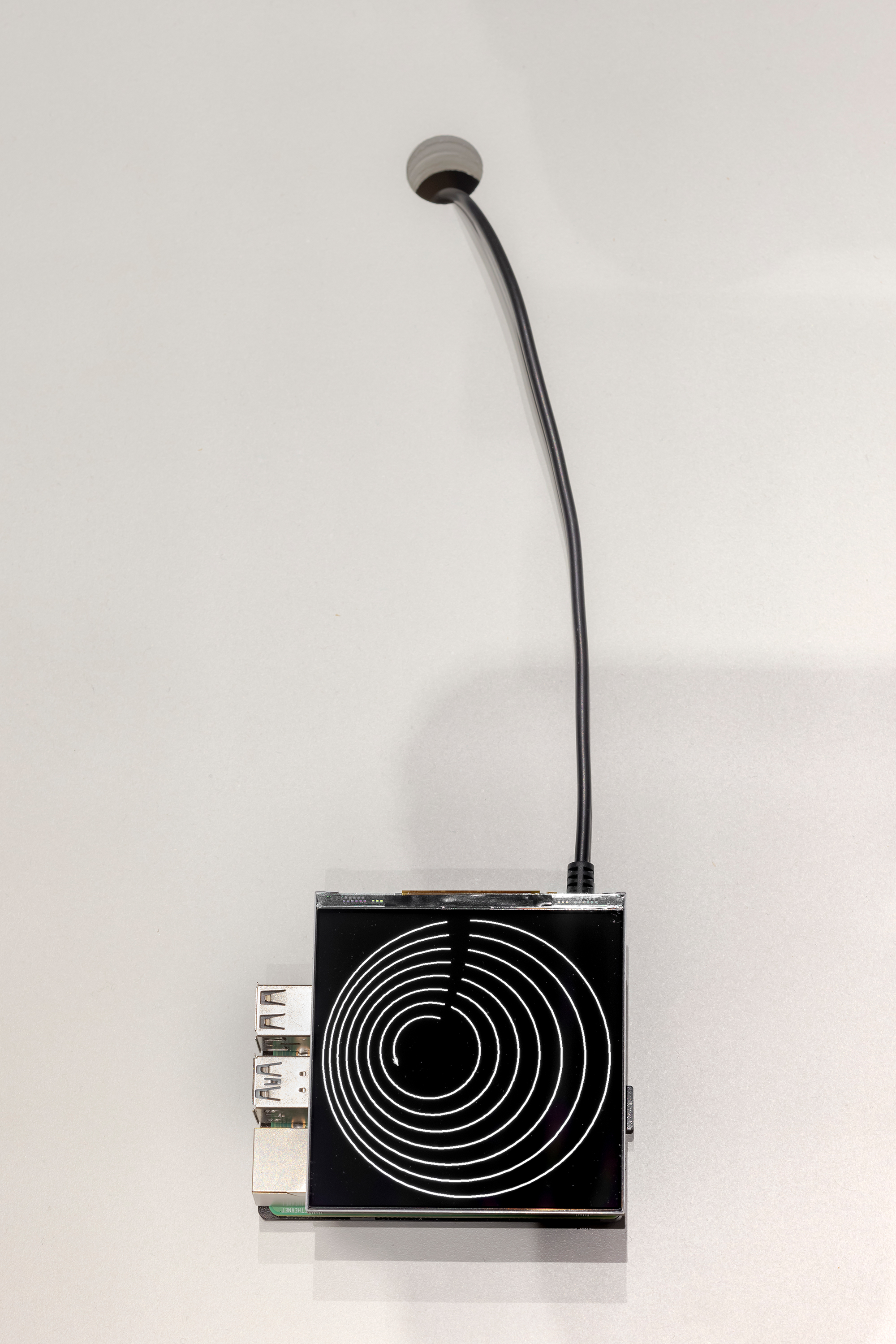

DO WHILE TRUE. Photograph by Toni Hafkenscheid.

The components of Matt's installation showcase the ways computers can turn words and language into a creative force. One of his works, titled DO WHILE TRUE, consists of a small, black-and-white computer display connected to a tiny computer. Using Logo, a computer programming language that allows users to draw vector graphics with relative ease, he made the display show a looping animation of 10 concentric circles. It's a reference to Ein Sof, a Kabbalah concept related to God's infinite nature.

Halted Moment, Executable. Photograph by Toni Hafkenscheid.

Another work, Halted Moment, Executable, is an LED matrix — another type of computer display — embedded in the surface of a table made to resemble the tiled floor of a server room. A few words at a time, the matrix tries to display the complete text of The Secret Miracle, a short story by Jorge Luis Borges. In the story, the titular "miracle" is that a playwright, sentenced to death by the Nazis during World War II, is granted a mystical yearlong stay of execution so that he can finish writing a play.

Like the story's main character, Halted Moment, Executable needs plenty of time to complete its important work. The display is programmed to scramble the story's lines and paragraphs, making them unintelligible. Only once per year, in a seemingly miraculous (but actually preprogrammed and fully automated) occurrence, do all the words appear in the correct order.

Oscar Alfonso

The idea for Oscar's project, No estoy seguro en nuestros nombres / I’m not sure I remember all of our names, sprung from a literal seed — an avocado seed.

"At the beginning of the pandemic, I started growing plants again, which is what I've done habitually, without realizing it, everywhere I've moved," Oscar says. "As I was growing these avocado trees, I started thinking about everybody that I was no longer close to — that I hadn't spoken to in a while, or that I was physically not close to."

Oscar's avocado plants.

Oscar began reaching out to people he knows, or used to know, including close family members, friends, old coworkers, and former lovers. "I wanted to consider relations as being more than the obvious close friends and family," he says.

He sent out a total of 210 messages, each one inviting the recipient to share a story, or a bit of knowledge, with the avocado trees. He asked that the responses be somehow related to one of five avocado-appropriate themes: obsolescence, travel, diaspora, expectation, or stationariness. In return, he received about 85 responses, mostly letters addressed directly to the avocado plants. Some of the responses were less straightforward — for instance, the one from Oscar's five-year-old cousin in Mexico. "He decided to read a children's book that I had gifted him," Oscar says. "But he can't read English, so he's reading this English-language book from memory, in Spanish. He's got the story, but bits are missing."

Left: An avocado plant and children's toys. Right: A portrait of Oscar as a child.

Oscar compiled all the responses into a book. He will complete his project with a live, online reading of that book, at 1 p.m. on June 5. The avocado trees will be present to receive the collected wisdom.

For details on how to join the reading, visit the exhibition's event page.

Sophia Oppel

Sophia was interested in the way surveillance capitalism controls and documents human bodies, rendering them legible. Her project, being both opened up and flattened, makes this type of surveillance visible and literal by borrowing some of the visual and auditory elements of an airport security checkpoint.

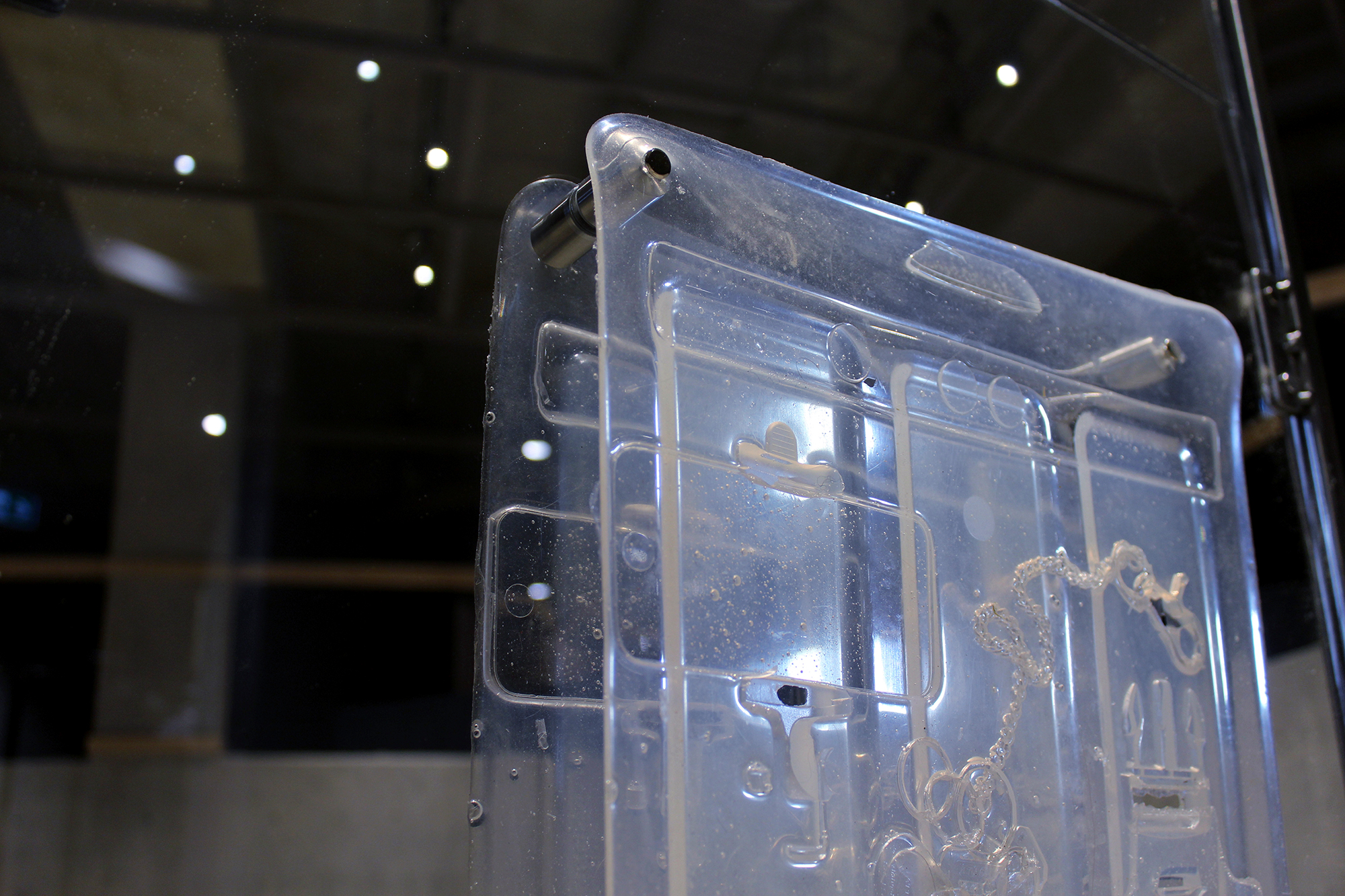

The two-way mirror assembly. Photograph by Toni Hafkenscheid.

At the centre of her installation is a six-foot-by-six-foot metal frame with two-way mirrors mounted in it — the same kinds of mirrors security officials would use to observe suspects without being observed themselves. Mounted to the mirrors are a series of silicone casts of various objects, arranged as if unloaded into airport security bins. A pair of rear projectors cause the casts to light up in sync with a voiceover, coming from a set of speakers. The disembodied voice makes cheerful-sounding, elliptical comments about surveillance culture ("a transparent body is a disciplined body") and commands the visitor to move around the space. The area is illuminated with Verilux HappyLights, a type of light fixture marketed as a treatment for seasonal affective disorder.

A silicone cast. Photograph by Toni Hafkenscheid.

"Sites of capitalist consumption are increasingly equipped with surveillance technologies," Sophia says. "My work is a critique of these things, but it's a complicit critique. The notion of being rendered legible is disturbing, but there's also, at least for me, a desire to be perform legibility and transparency in sites like the airport and in digital networking, where you exchange transparency for access."

"Desire is woven through this. The desire to be transparent is this very insidious thing that many people internalize."

Simon Fuh

"I used to throw parties in my hometown, Regina, Saskatchewan," Simon says. "When I moved to Toronto, I found myself totally immersed in my graduate studies, but also really missing that social aspect. Throwing parties really gave me meaning at that time in my life." For his installation, Memory Theatre, he created an immersive environment intended to give a visitor the somewhat paradoxical feeling of simultaneously being at a party in the present, and recalling a party that happened in the past.

A visitor would see this upon entering the exhibition space. Photograph by Toni Hafkenscheid.

The experience begins when a visitor enters a darkened room. (Simon's installation space was the Daniels Building's main hall.) The sounds of rain and footsteps emanate from speakers in the ceiling.

Inside the darkened room is a sculpture — a square, 12-foot-by-12-foot box with a faint greyish light spilling out from one side. On closer inspection, the visitor discovers that the light is coming from an open door in the side of the sculpture.

Inside the sculpture. Photograph by Toni Hafkenscheid.

Within the sculpture, the aural landscape changes. The visitor hears a murmured phone conversation between two friends. One friend is telling the other friend, in almost too much detail, how to get to an after-hours club called Checkmate. As the audio recording progresses, a soft, low-register bumping, like the bass from distant dance music, begins to rattle the sculpture's walls. Meanwhile, the description of Checkmate gets more and more specific. A voice describes the bouncer, the music, the mood of the room. The party always remains just out of reach, on the cusp of perception.

For Simon, the work is at least partly a response to the pandemic, which has made the very idea of an after-hours party something of a distant memory — the type of memory one might have to fumble around in the dark to locate. "It's totally a nostalgic project," he says. "But it places the nostalgia in the present tense. We're activating memories from the past as though they're happening right now. That way of enacting memory is a really interesting way of thinking about memory's potential for reinvigorating a future event."