13.10.21 - MLA Field Studies I: How “landscape detectives” trace Toronto’s hidden rivers and lakes

Popular depictions of Toronto paint the city as a skyward-reaching metropolis of concrete and glass. But beneath the built environment, complex ecosystems are hidden in plain sight — and to find them, says sessional lecturer Michael Ormston-Holloway, all you have to do is look. And bring a sketchbook.

As part of the Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA) program, Ormston-Holloway led Field Studies I, which encouraged new students to critically examine the landscape while capturing their interpretations in drawing. Over the course of a week in late August, students were asked to observe the living and non-living elements of the landscape through a different lens: Ormston-Holloway challenges his students to examine the landforms, soil, drainage and vegetation of the city.

“One of the principal goals of the course is to have you be landscape detectives,” he adds. “Landscape architects need to be so many things. It’s a field ecology course, so we’re not spending as much time looking at deficiencies in concrete as much as living systems. Why is one living system a healthy ecological model? Why is another more contrived or gestural?”

Last year, with courses being delivered online, Field Studies I was held remotely, with students creating one-kilometre corridors of study beginning at their front doors. This year, with in-person activities slowly returning, Ormston-Holloway started the course by bringing students to sites around the city: first, they visited midtown’s Wychwood Park, a former artists colony featuring many homes designed by British-Canadian architect Eden Smith. Next, students were shuttled to the rugged Scarborough Bluffs, known for its scenic views of Lake Ontario. Finally, students headed downtown, riding the ferry to the Toronto Islands.

This isn’t exactly tourism — the long pants and closed-toe shoes, even with the humidity pushing temperatures past 40 C, indicate there’s more afoot. In actuality, Ormston-Hollowell is leading students across the shoreline of Lake Iroquois, a proglacial lake that once sat atop parts of the city. The contours of the ancient lake are easily visible in the city’s bluffs and escarpments, but the region’s glacial history is also relevant in less obvious ways: it determines the structure, texture and pH of the soil beneath the group’s feet.

It's not the only thing the MLA detectives investigated. Early on during the group’s walks, Ormston-Holloway directs attention to the sound of water rushing underneath certain manholes. That’s the sound of Garrison Creek, a major waterway that — to the uninitiated — is largely invisible. And that’s by design.

“It’s about how humans manipulate urban environments,” he says. “In the time of water-borne illnesses, water wasn’t coveted at all. We added waste to our water systems, then piped and buried them so we could build a city on top of it. That’s completely counter to how we would design now. And thank God for that.”

The design decision of city planners — and previous generations of landscape architects — looms large, as the city’s natural systems are interconnected in ways many might not imagine. The Toronto Islands, once fed by sediment from the eroding Scarborough Bluffs, are now being “starved” by the development of the Leslie Street Spit, a man-made headland that juts out from the western corner of Ashbridges Bay. It’s proof that, for landscape architects, interventions can have cascading effects.

“This sustainably fed system is now gone,” says Ormston-Hollowell. “So now we, as people, need to step up and manage it in way that’s resilient and sustainable. Or at the very least, more sustainable.”

The conversations, and sketches, continued the following day at the Evergreen Brickworks, a former quarry site that now features trails, ponds and wetlands. There, the group snaked their way through the Don Valley’s sub watershed — land where water flows through before it reaches Lake Ontario — and worked their way towards Corktown Commons, at the mouth of the Don River. After days of walking, the conversations start to get “really good.”

“Often, I teach in a way that gets a concept across, but [in the field], biology doesn’t always behave itself. And inevitably, a student will have a question that bends the conversation in certain ways,” he says. “That’s the real value of going on a big walk every day. [In the Don Valley], we start to talk about the importance of parks to floodplains, and how we develop these systems. To get a bit more technical, we look at flood protection landforms that trigger planning that wouldn’t have happened otherwise.”

In the field, Ormston-Holloway, who is also a partner at landscape architecture firm Planning Partnership, encourages his students to sketch as he might at his practice: sometimes, they toy with the speed of sketches. They use heavier and lighter leads. Some include richer detail. It’s an exercise that helps students learn how to inventory what they’ve seen — and back on campus, they’ll use digital tools, like AutoCAD, to design and draft their findings.

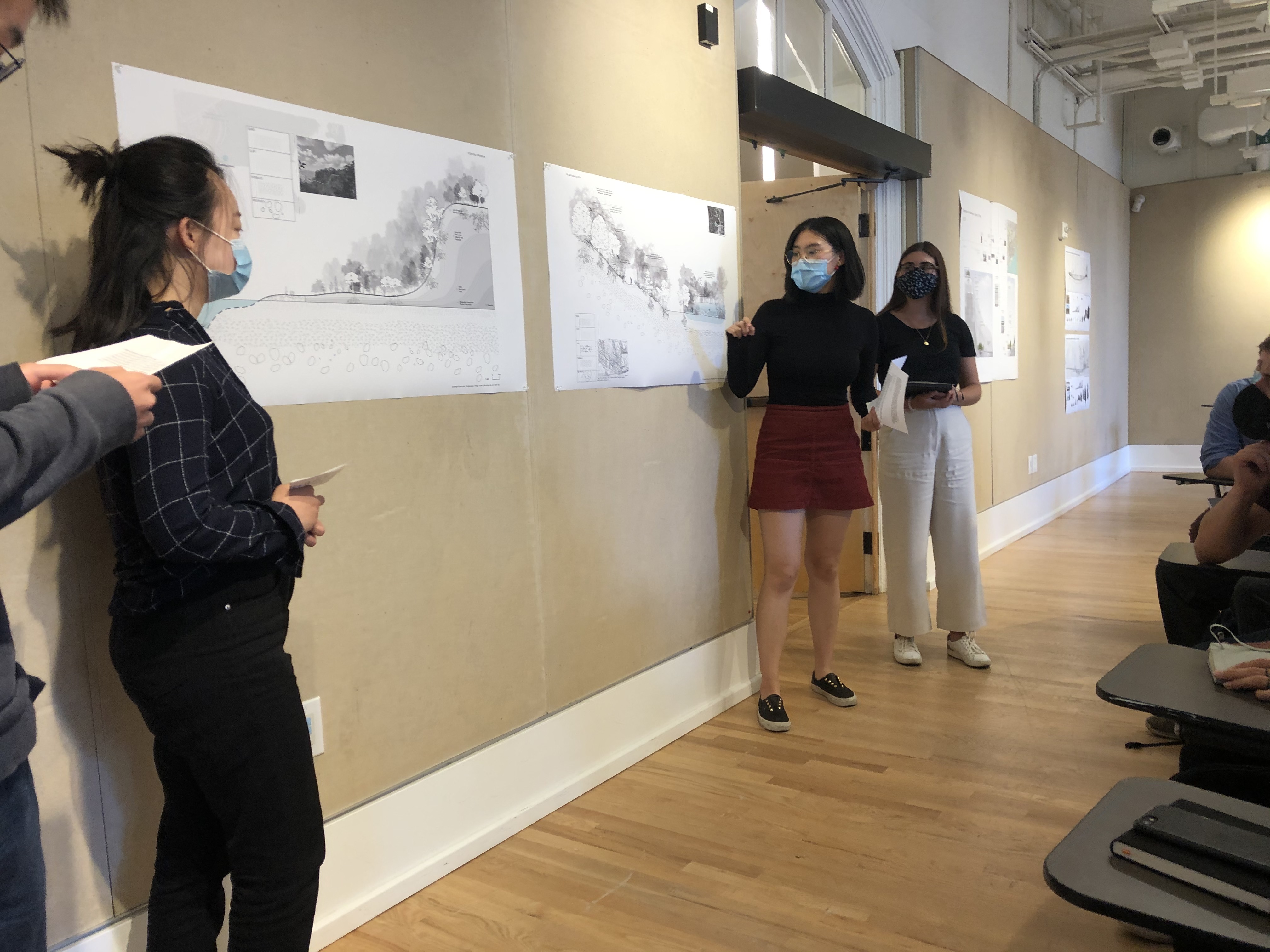

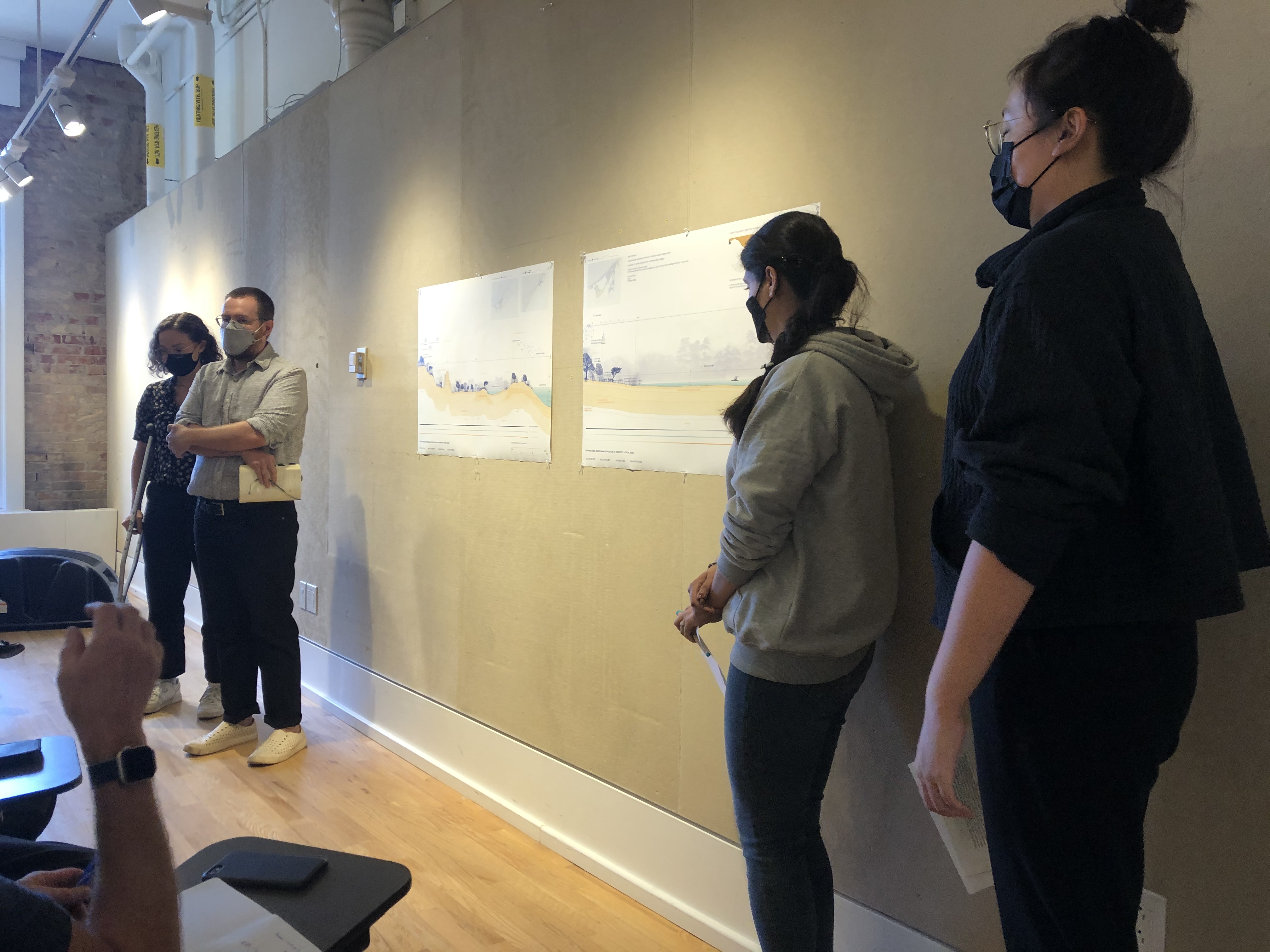

On the final day of Field Studies I, those sketches are rendered beautifully in panels, affixed to a classroom wall. And while Ormston-Holloway has run through similar activities for 17 years, this part never gets old. “I’ve seen a lot of students [come through this field course], and the one thing they’ve had in common is the pride they feel when they pin up their final panels,” he says. “The struggles many students go through — some haven’t spent time with Adobe or CAD software — it all happens in a week. From the start, to five days later, they produce something that’s polished. Something they’re extremely proud of.”

Welcome to the field.