16.09.20 - Daniels alumnus Janis Kravis, who brought Scandinavian style to Toronto, dies at 84

Janis Kravis, who graduated from the Daniels Faculty — then known as the University of Toronto School of Architecture — in 1959 and soon afterward founded Karelia, an influential textile, furniture, and housewares store that helped popularize Scandinavian design in Toronto, died on July 16, at the age of 84.

Kravis was born in Latvia in 1935. In 1944, during the last months of World War II, he fled with his family to Sweden ahead of the advance of the Russian army. Six years later, the Kravis family boarded a ship bound for Canada, where they would live the rest of their lives.

In 1960, when Kravis opened Karelia in the vestibule of a friend's beauty parlour at 729 Bayview Avenue, Toronto was a much different place. Downtown was an expanse of low- and mid-rise buildings, churches, and parking lots. High-end dining was steak, steak, and more steak. Shopping and many forms of public entertainment were banned on Sundays.

Karelia was like a splash of bright-orange paint on the city's beige public façade. Kravis had learned about Finnish architecture and design during his studies at U of T. After he graduated, he began writing to Finnish manufacturers, requesting catalogues and samples. The products — brightly coloured textiles and elegant, minimalist housewares — were like nothing else available in Canada at the time. He and his business partners (his sister, Gundega, and their friend Solveig Westman, both of whom were later bought out by a third partner, Björn Edmark) began importing items to stock Karelia's shelves.

Karelia, in its Gerrard Street West Village location.

Before long, Karelia moved out of the beauty parlour and into its own shop on Elm Street, in the middle of what used to be known as Gerrard Street West Village. The neighbourhood, now largely demolished and redeveloped, was at the time a bohemian hangout, favoured by artists, writers, and other creative types. It turned out to be an ideal place for Kravis's Scandinavian design sensibility to take hold and gain acceptance.

Karelia also received an unexpected boost from another part of the city. In 1961, construction began on Finnish architect Viljo Revell's bold, curvilinear design for Toronto's new city hall. The new civic structure was a monumental advertisement for Scandinavian design — and, more significant for Kravis and Karelia, it brought Revell to Toronto.

"I got to know Viljo Revell and his team of architects when they were working on the Toronto City Hall," Kravis would later write. "They literally opened up their kitchen cabinets and showed me dishes by Kaj Franck for Arabia, glassware from Iittala, as well as fabric and cushions from Marimekko. They told me about Armi Ratia and Timo Sarpaneva, Tapio Wirkkala, Artek, Antti and Vuokko Eskolin-Nurmesniemi, Metsovaara, Fiskars, Haimi, Muurame and many others. I had just sold my secondhand car and was planning my first trip to Finland."

Karelia rapidly expanded its product lines. The shop became particularly well known for its selection of designs by Marimekko, the legendary Finnish textile house whose bright patterns played a role in defining the vibrant, optimistic style of the early 1960s. Kravis met Marimekko co-founder Armi Ratia on a buying trip to Finland, and the two remained friends until her death in 1979.

Top: Karelia's Front Street location. Bottom: The fabrics department in Karelia's Manulife Centre location.

Kravis closed the Gerrard Village shop and moved Karelia into a new and more prominent storefront in Lothian Mews, a stylish shopping centre located near the then-burgeoning neighbourhood of Yorkville. Soon afterward, he opened a second Karelia location on Front Street, near St. Lawrence Market. The shops were becoming popular with the city's design cognoscenti.

Bruce Kuwabara, now a partner at KPMB, was, at the time, an architecture undergraduate at U of T. Like many of his contemporaries, he found himself drawn into Karelia's orbit. "The girlfriend of one of my best friends worked at Karelia," Kuwabara recalled recently. "So I went down there, and everyone was hip and swinging, and wearing miniskirts, bright colours, white go-go boots. It was flamboyant. It was really everything Toronto was not. It was beyond fashion-forward. Nobody had ever seen anything like it."

Parties at Karelia.

Kravis's sensibility began to rub off on Toronto designers in subtle ways. "He swung the pendulum in the direction of modern, Nordic architecture," says Leslie Rebanks, an architect who befriended Kravis in the 1960s and remained his frequent dining companion until weeks before his death. "He influenced a lot of influential architects. We all went to Karelia. We owe a lot to him for introducing the public to the idea that modern architecture was a philosophy worth following — a philosophy of economy, of materials, of line and expression."

Another influential personality who became a Karelia customer was George Minden, owner of the Windsor Arms Hotel. It was through Minden that Kravis was offered an opportunity to make another memorable contribution to Toronto's emerging cosmopolitan culture: he became the architect for Three Small Rooms, a restaurant located on the lower level of the Windsor Arms.

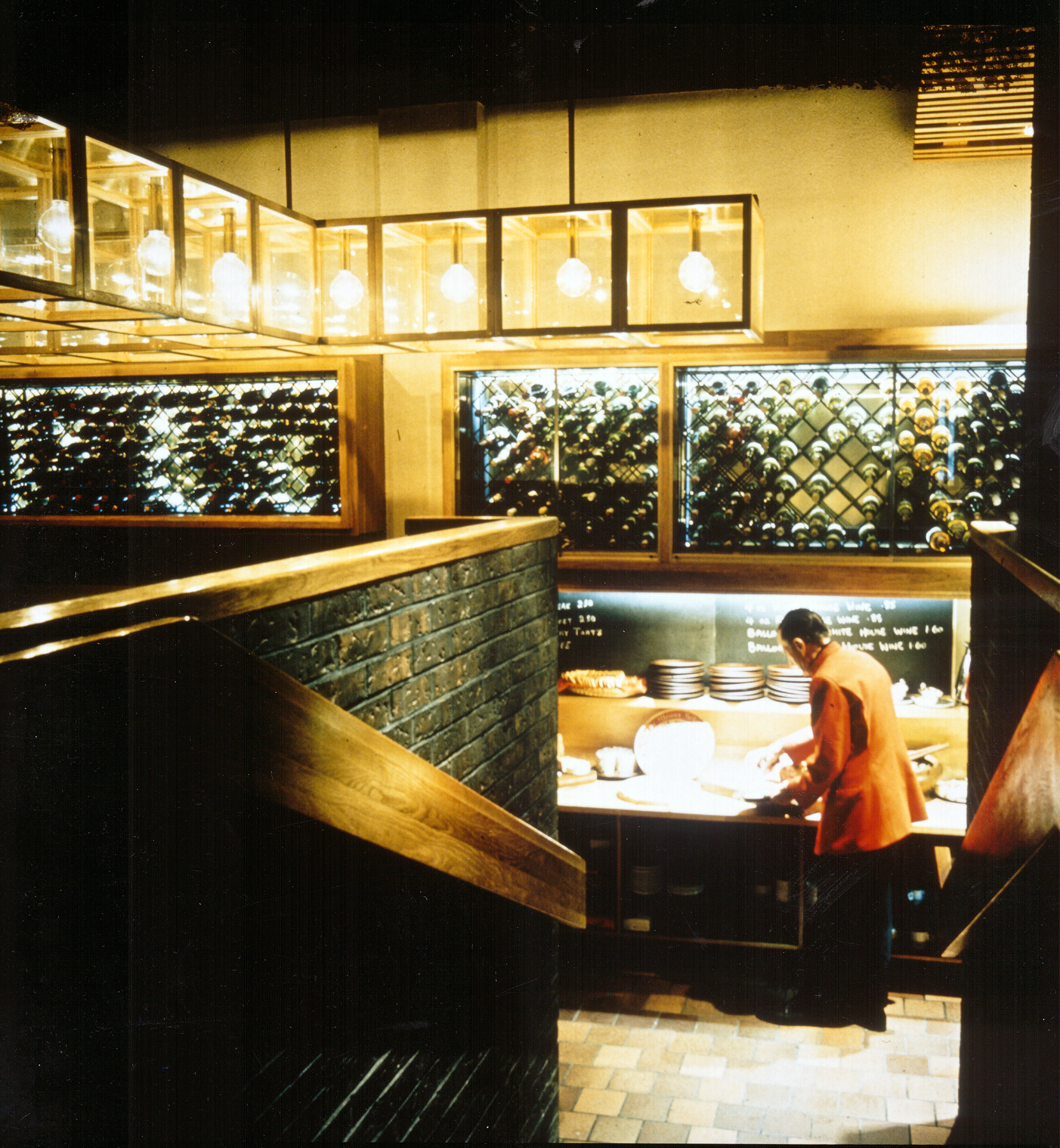

Kravis designed or hand-selected every aspect of the restaurant's interior, including the uniforms worn by staff members. The space was, as implied by the name, divided into three distinct dining spaces, each with its own look. The main dining area was lined with mahogany, its rosewood tables polished to a high gloss. The chairs, also made of mahogany, were designed by Kravis himself. A "grill" area was decked out with leather and dark wool, with Marimekko fabrics on the walls. The restaurant's intimate wine cellar was swathed in brown brick and sleek white oak, and topped with a modernist chandelier.

Top: The main dining room in Three Small Rooms, with chairs designed by Kravis. Bottom: The entrance to the wine cellar at Three Small Rooms.

Three Small Rooms, which opened in 1966, provided a type of sophisticated, design-forward dining atmosphere that was rare in Toronto at the time. An early review by Robert Taylor in the Toronto Star complained about the high prices but praised the "handsome wining and dining complex."

"It will be, for the reasons cited above, Toronto's most discussed dining-out place in the weeks ahead," Taylor concluded.

Joanne Kates, the Globe and Mail's longtime food critic, worked briefly as a cook at Three Small Rooms, and later wrote of the restaurant: "[It] was the place responsible for the discreet civilizing of the bourgeoisie." (The restaurant closed in 1991 after a series of changes in the ownership of the hotel, and its passing was mourned by gourmands and architecture lovers alike.)

Over the following decade, Karelia moved again, from Lothian Mews to the newly completed Manulife Centre at Bay and Bloor streets. Kravis opened two satellite stores, one in Vancouver and one in Edmonton, before shuttering the entire Karelia chain in 1980 amid financial troubles.

After the collapse of his retail empire, Kravis continued to practice architecture as a consultant for public and private clients. He became interested in sustainability and environmentalism — topics he wrote about frequently on his website. In 2012, he revived the Karelia name and logo on a new Toronto restaurant, Karelia Kitchen, operated by his son Leif and Leif's wife, Donna Ashley. The restaurant, known for its colourful platters of Scandinavian pickles and smoked fish, earned positive reviews before closing permanently in 2018.

Kravis was predeceased by his wife, Helga. He is survived by his three sons, Leif, Nils, and Guntar, and his sister, Gundega.

Top image: Janis Kravis, photographed in Stockholm in 2017. All photos courtesy of Guntar Kravis.