17.02.20 - Christine Sun Kim leads a powerful evening of art and learning about deafness

On Thursday evening, the main hall at the Daniels Building was full to capacity. Throughout the crowd, people were chattering excitedly in American Sign Language. The evening's guest of honour was Christine Sun Kim, a multimedia artist whose work frequently draws inspiration from deafness and deaf identity.

Kim was born deaf, and she often uses sound as an artistic medium. This isn't as paradoxical as it seems. Game of Skill 2.0, an installation she staged at MoMA PS1, was an interactive system in which museum visitors could hear a story read aloud from an electronic device, but only by maintaining physical contact between a sensor-equipped probe and an elevated strip of velcro. (It's easier to understand if you just watch the video.) The awkwardness of the arrangement made it necessary for visitors to acquire a skill in order to hear the story — and that was precisely the point. Kim has created lullabies and operas. Even when she does visual art, it often explores ideas about the way sound behaves in the world — like her famous pie charts, which cleverly quantify the irritations of navigating a hearing-oriented world as a deaf person.

Her work is starting to become better known. A giant mural of hers hung on the outside of the Whitney Museum in 2018. Earlier this month, she sang The Star-Spangled Banner and America the Beautiful in sign language at the Super Bowl — then wrote a New York Times op-ed in which she critiqued Fox's decision not to air the majority of her performance.

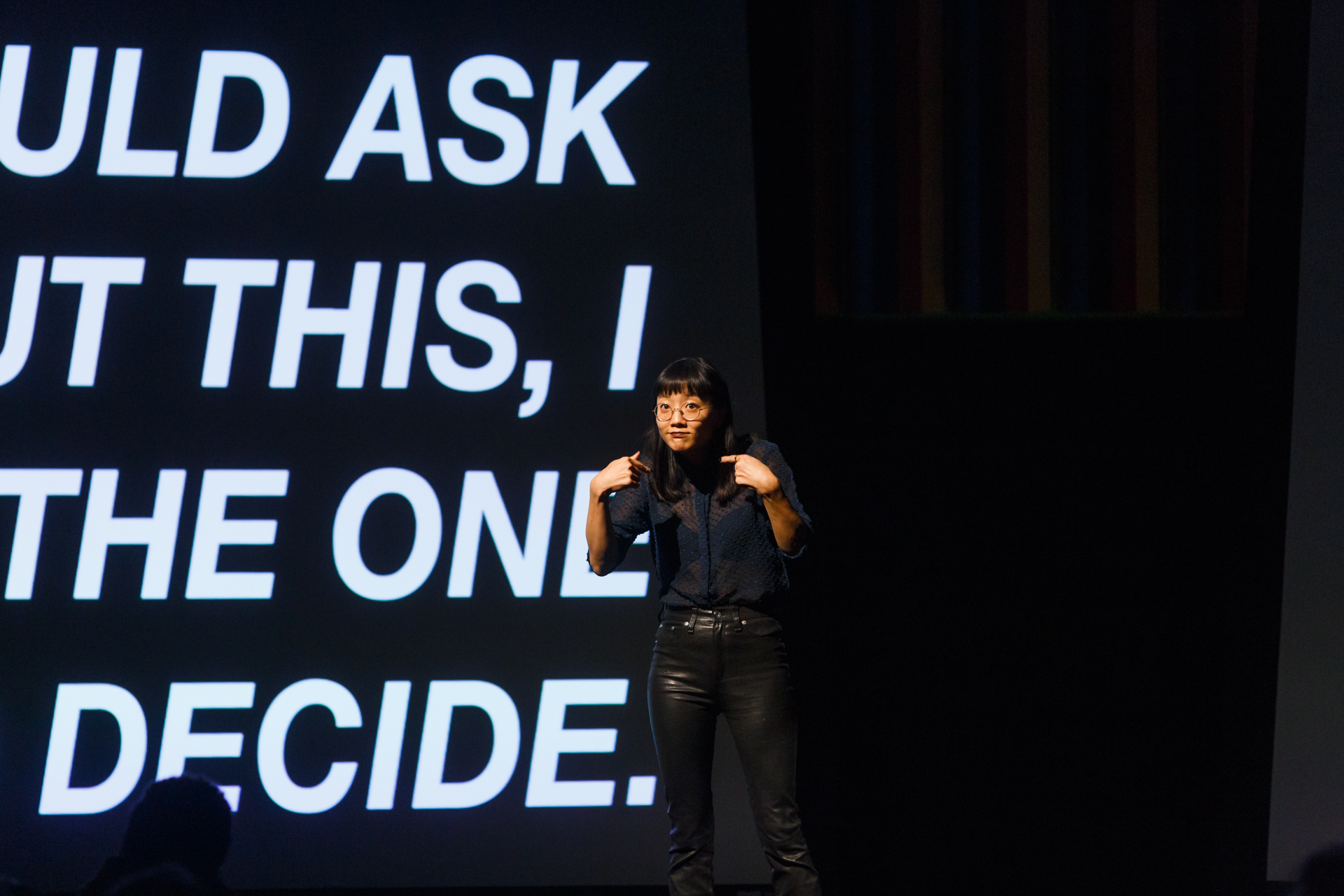

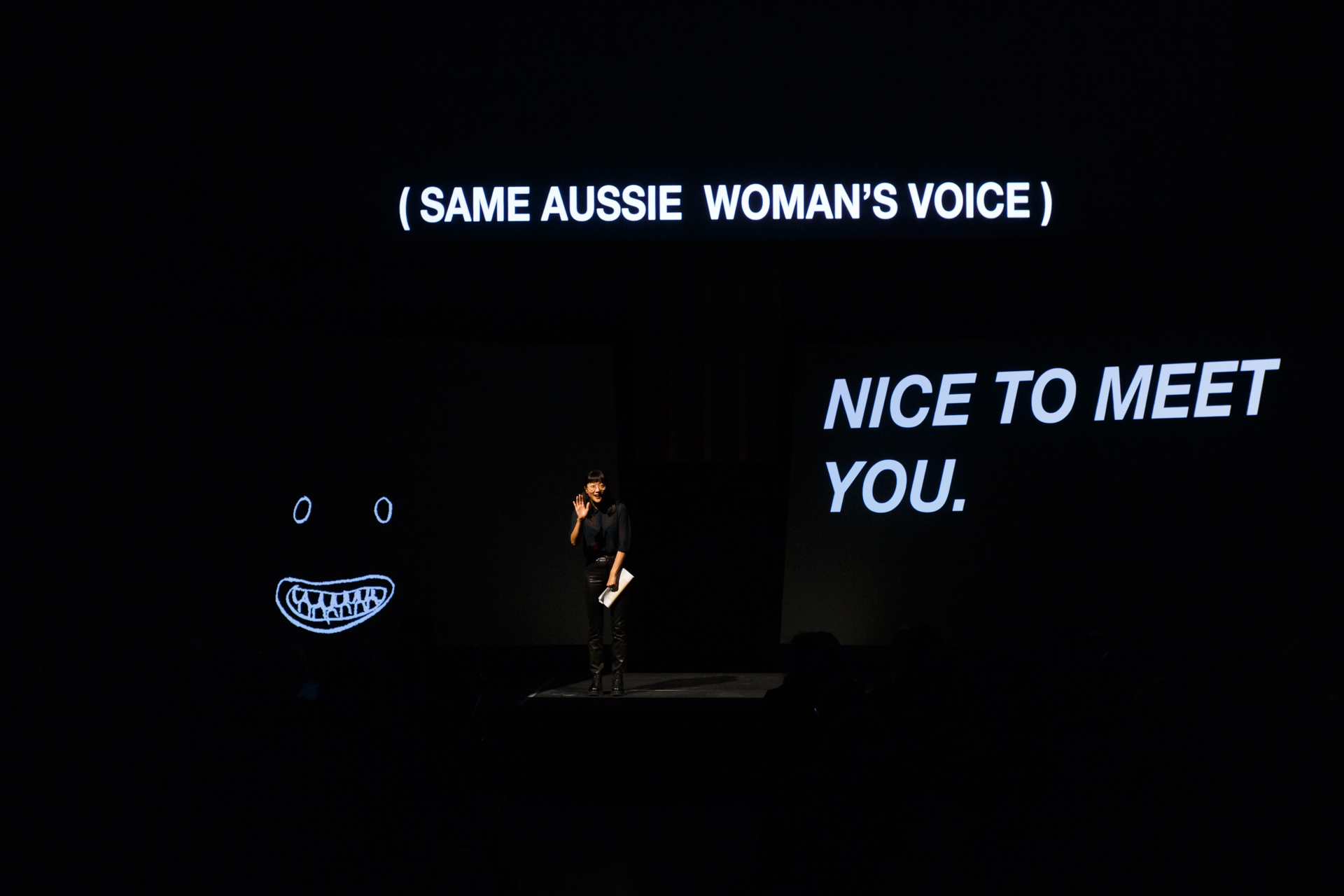

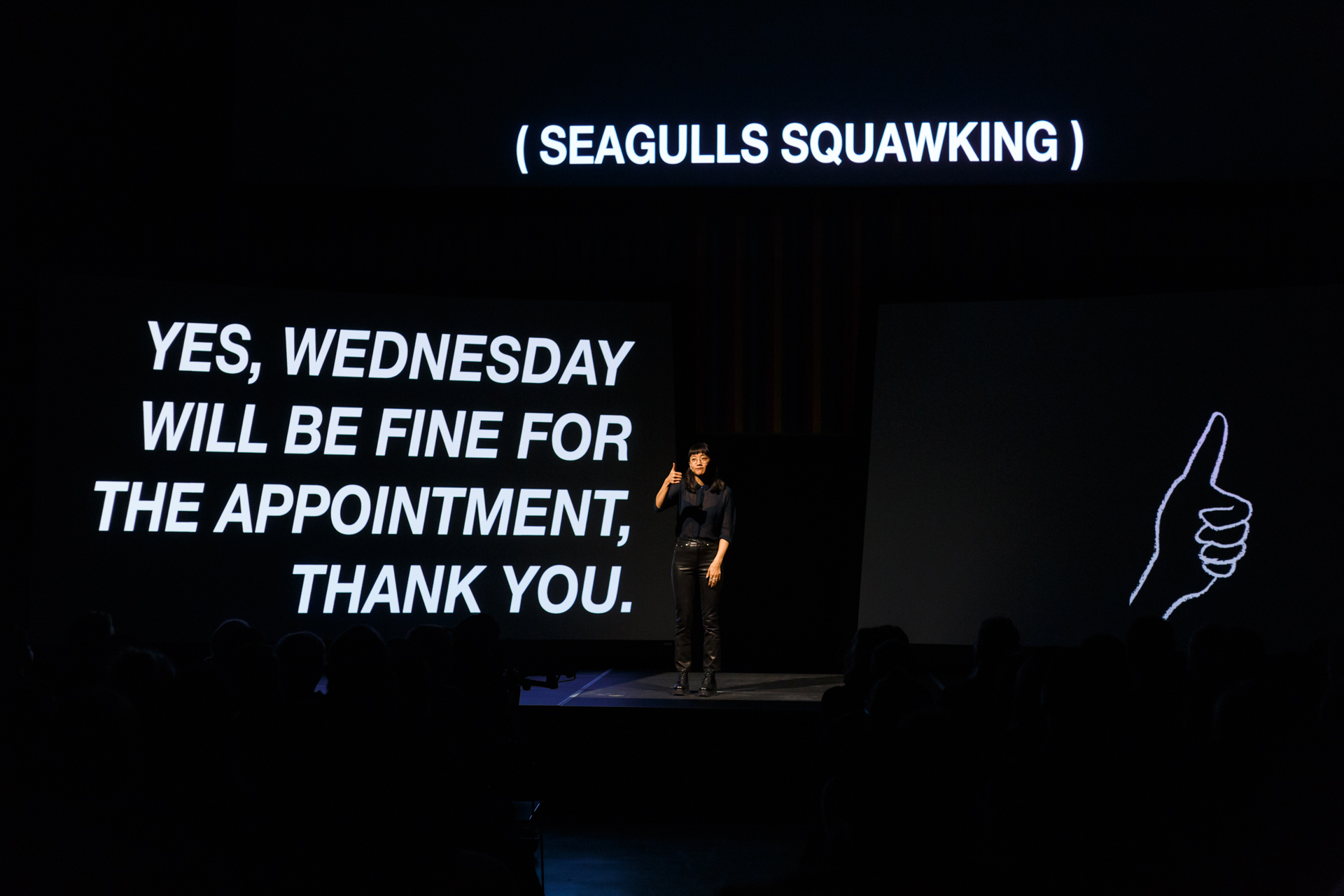

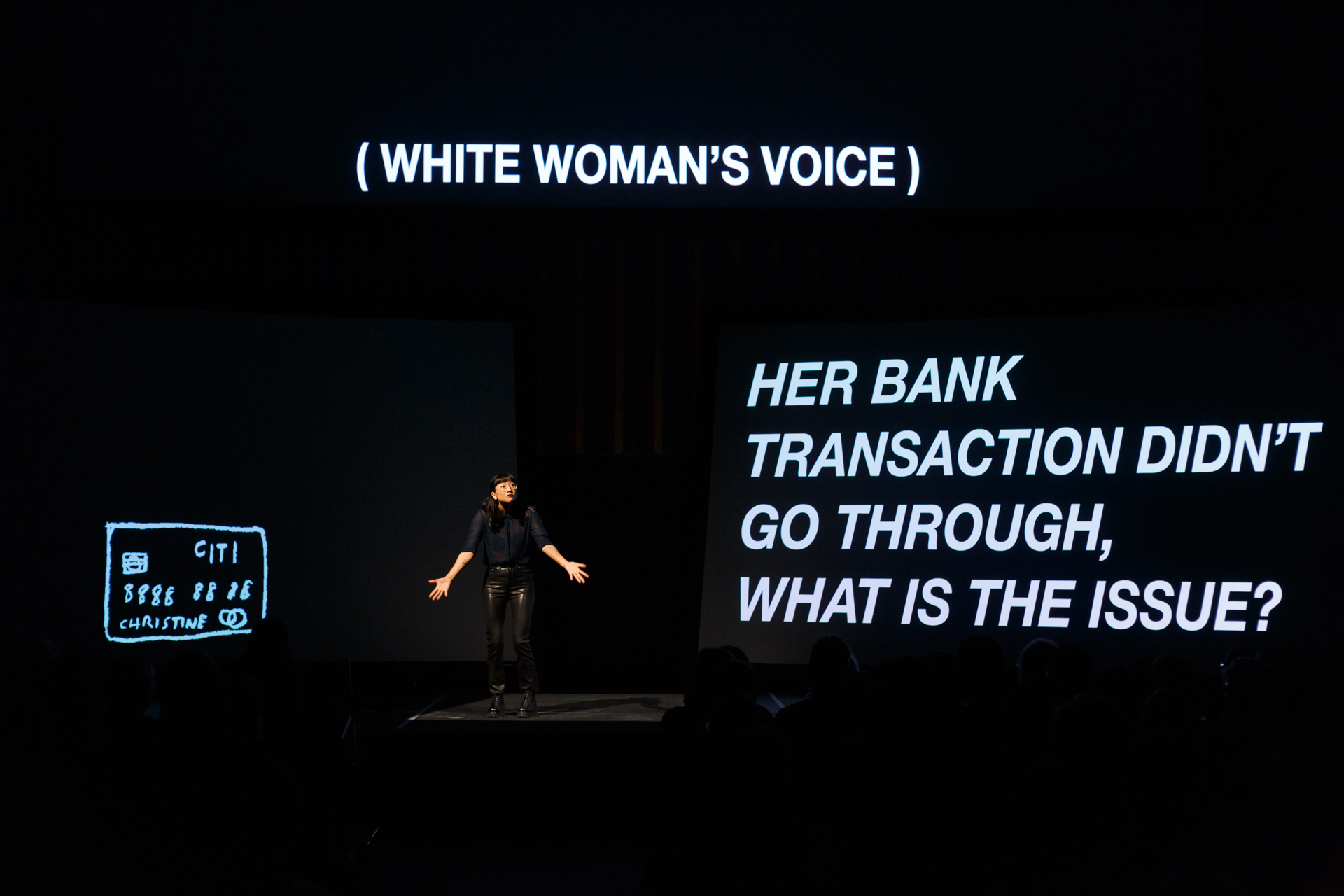

During her appearance at the Daniels Building, which was part of the Daniels Faculty's "Hindsight is 20/20" public programming series, Kim presented a multimedia piece of performance art called Spoken on My Behalf. The work consisted of three large video projection screens that displayed white captions on plain, black backgrounds. As the captions flashed by, they began to accrete into an essay about what it's like for Kim to rely on family, friends, and acquaintances to speak for her in social situations. The experience, she seemed to suggest, can be both frustrating and liberating.

The hall was darkened, and the performance was silent, except for occasional recorded voices saying the kinds of things that deaf people sometimes ask (or don't ask) others to say for them: "She'll have a pilsner." "She needs to go the bathroom." Each time one of those voices spoke, Kim would step into a lighted area on the stage and gesture along. The nature of the complex relationship between the artist and her many surrogate voices was left to the audience to contemplate.

Here are a few photos from the night.

Many members of the audience were deaf, so dean Richard Sommer's introductory speech was interpreted into American Sign Language:

A trio of projection screens displayed captions and images, making the performance equally accessible to deaf and non-deaf audience members:

The only sounds were occasional recorded voices that seemed to be speaking for — or through — Kim. The sound captions on the upper screen were mostly drawn from TV shows Kim had watched, and weren't referencing actual sounds in the room. (There were no seagulls squawking when this photo was taken.)

Without signing a word, Kim eloquently communicated some of the frustration that is part and parcel of negotiating differences in communication style:

After the performance, she gave an artist talk in which she showed slides of some of her other work. As Kim signed, an interpreter voiced her for hearing audience members:

During a Q&A session, a few audience members posed their questions in sign language:

And at the end of the presentation, the audience applauded in sign language:

Photographs by Harry Choi.