10.11.20 - The long-delayed Master of Visual Studies graduating exhibition is finally happening

Last semester's Master of Visual Studies graduating exhibition was postponed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. But now, with the U of T campus once again open to small groups of visitors, the show is finally happening, a few months late.

The exhibition is an annual end-of-program showcase in which each year's graduating MVS students install their work at the University of Toronto Art Museum, where it can be admired by the public. The 2020 exhibition, which was originally scheduled to occur in spring, opened at the Art Museum on October 28 and will continue until November 21. Anyone who wants to visit the exhibition must pre-register for a time slot, and then obey the university's health and safety policies (including mandatory face mask usage) while on site. See the Art Museum's website for more details.

The exhibition includes the work of both studio students (who created original work) and curatorial students (who curated the work of others).

For anyone who needs more convincing to go experience the exhibition in person, here's a preview of some of what's on display.

The studio students

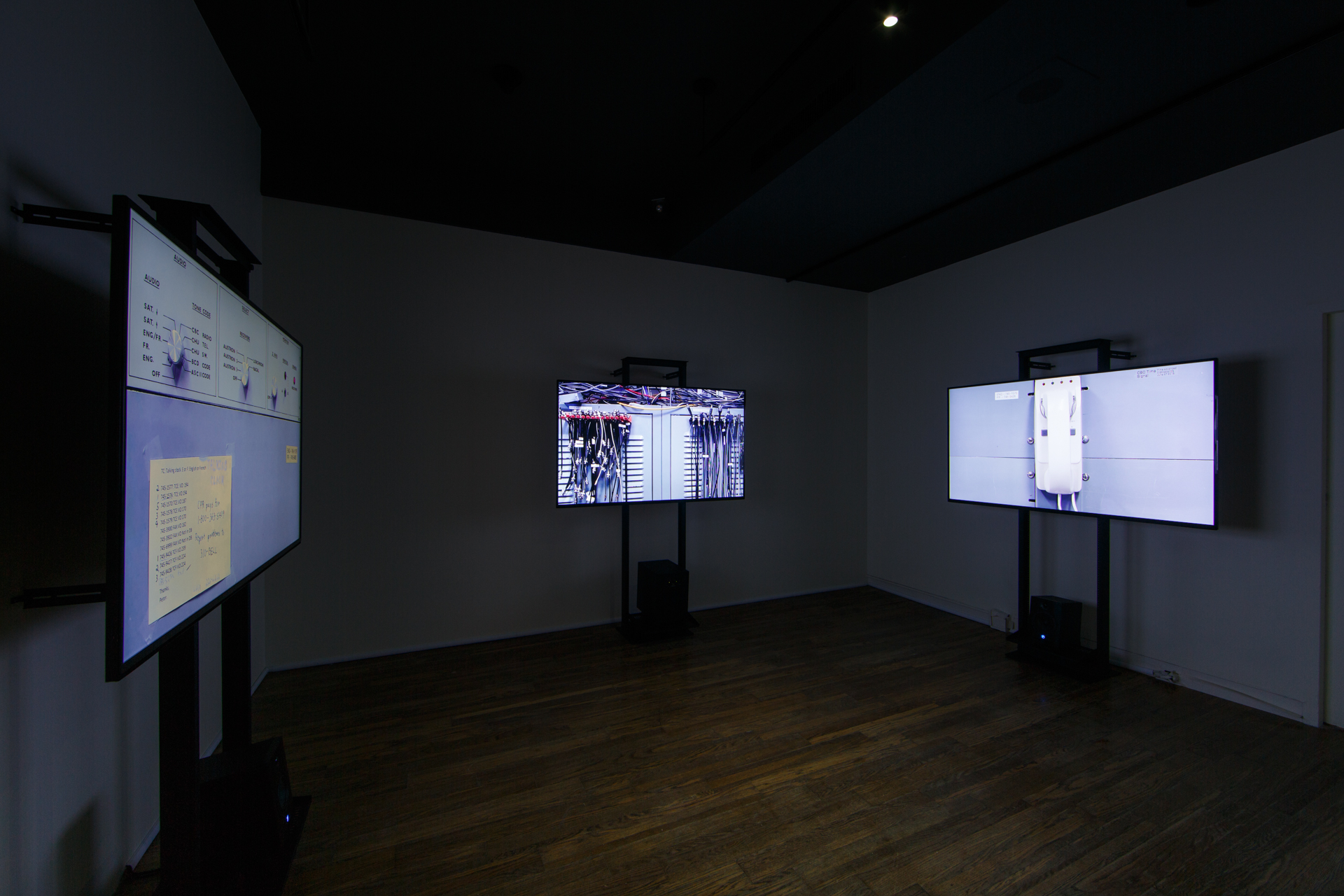

Emily DiCarlo's installation, titled The Propagation of Uncertainty, explores the way time works in the world. "I was thinking about a poetic distinction between how we, in our body, experience time, versus the external infrastructure of clock time," Emily says. "I'm interested in how those things are at odds and how they meet."

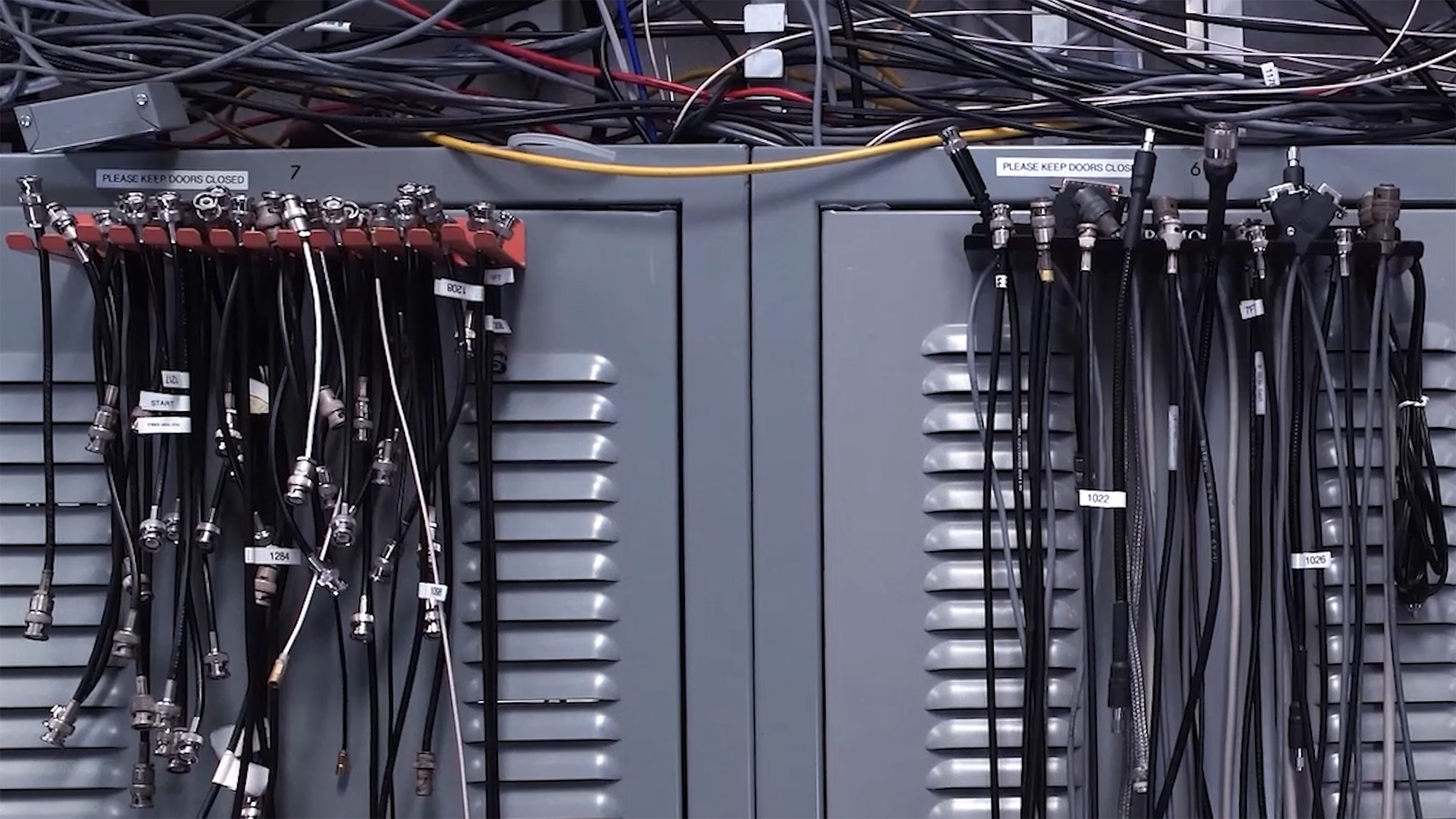

As part of her project, Emily visited the offices of the National Research Council, in Ottawa, where Canada's national time standards laboratory is located. There, a team of scientists maintains an extremely precise cesium atomic clock, which is part of a global network of similar atomic clocks that calculate Coordinated Universal Time, or UTC — a time standard used to synchronize timekeeping devices around the world.

Emily spent four hours filming in the laboratory and used the resulting footage to produce a three-channel video. A viewer sees the laboratory's dishevelled server racks and the odd bits of equipment used in the measurement of time. "I went in with the idea of surveying the space," she says. "It hasn't changed since the 1970s, so there is this really nice aesthetic that goes through it. You'll see a lot of poorly written notes hanging off things, and tangled wires. You can really sense the discord in the space, even though it's supposed to be the most precise temporal space in Canada."

The video barrage ends with an image of Emily on her back, on the laboratory's floor, breathing calmly among the equipment, as if to suggest that mechanical time and bodily time might not be totally at odds.

As part of the installation, Emily also created a website called Circular T: A Collection of Uncertainties. It's named after Circular T, a monthly time-adjustment memo distributed by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures. Emily's website mimics the formatting of the real Circular T — except, rather than information about nanosecond adjustments to atomic clocks, Emily's circulars contain poetry and haunting stories about time researchers pushed to extremes.

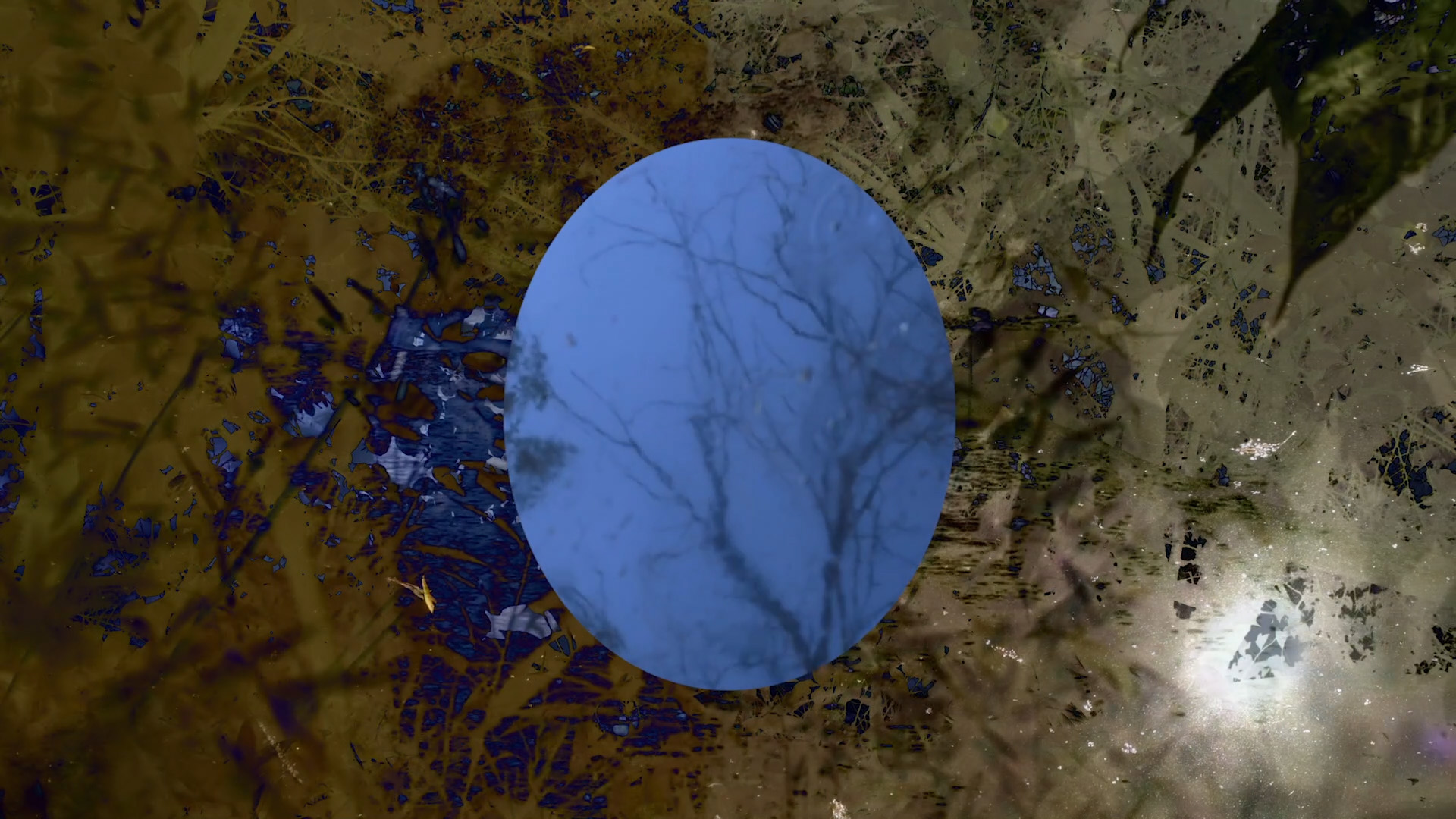

Chris Mendoza's installation, yet you dream in the green of your time, takes inspiration from Toronto's Don River. The Don was originally a meandering waterway, with natural curves, but it was partially straightened in the late 19th century as a way of facilitating industrial development. The city is now at work on an ambitious project to renaturalize the river's mouth and redevelop the surrounding area into a condo commuinity. Chris saw this time of change as an opportunity for artistic intervention.

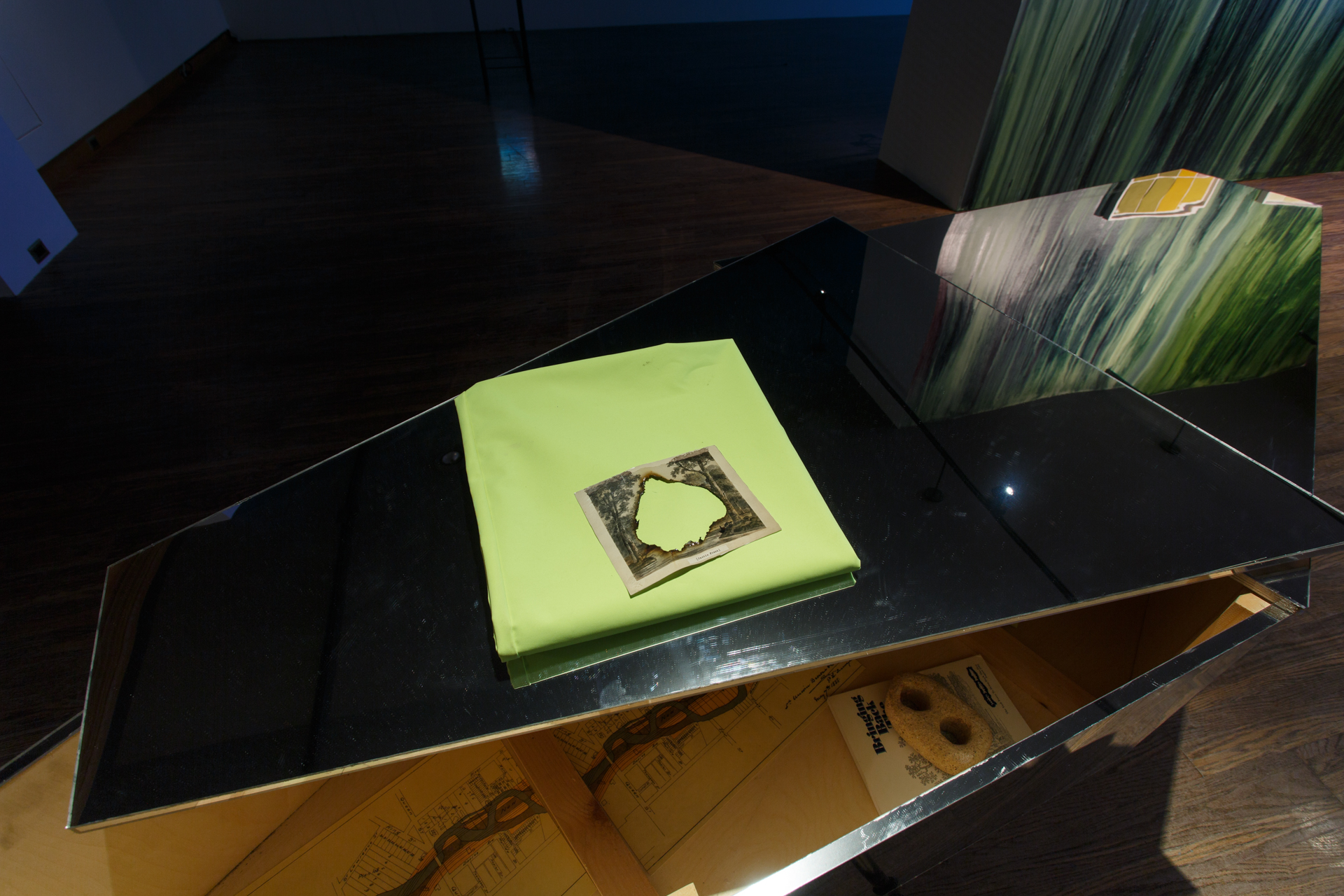

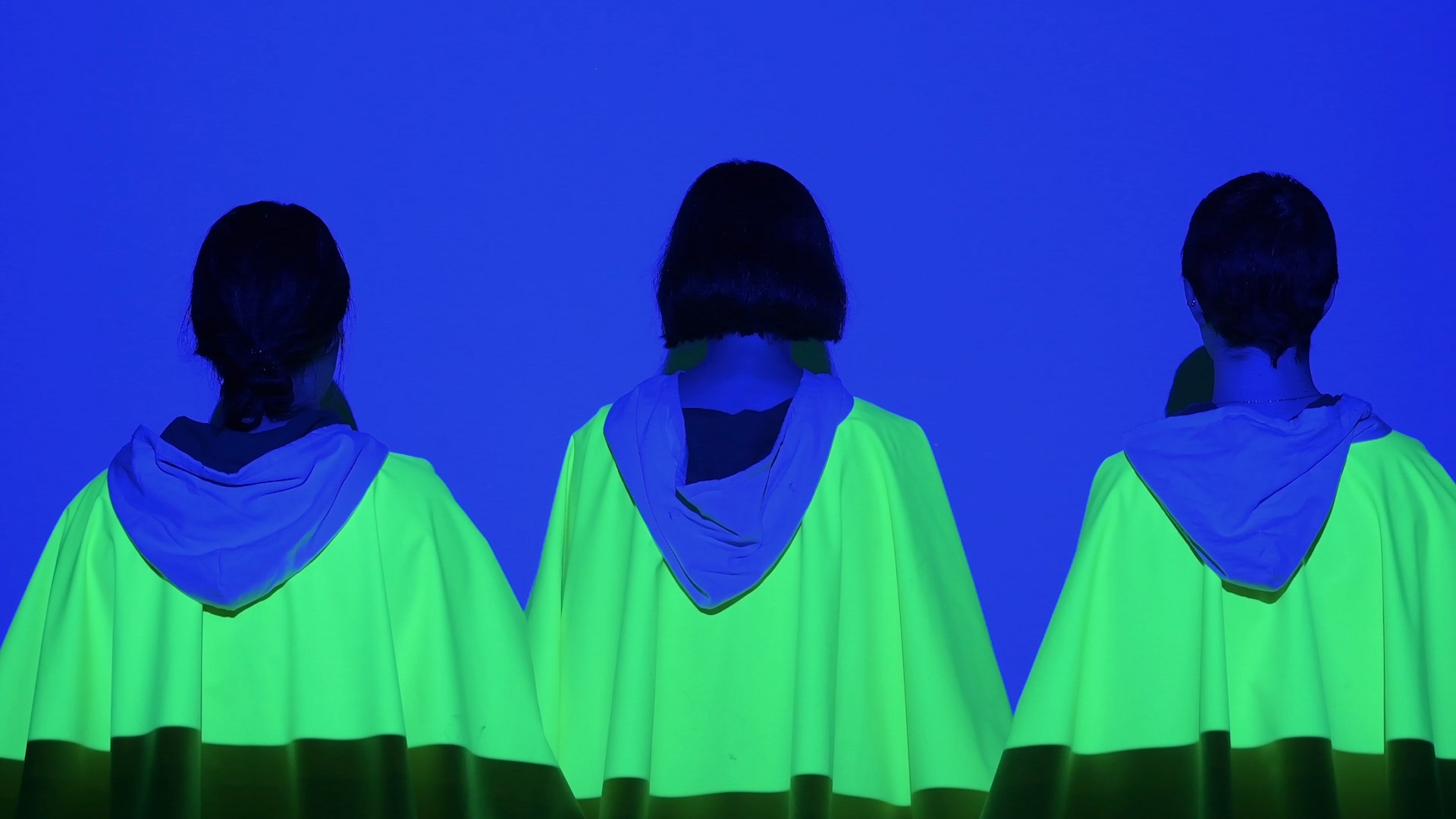

Taking inspiration from a 1969 protest against pollution in the Don River, during which participants held a mock funeral, Chris constructed a mirrored coffin. Dressed in a neon poncho that evokes both the high-visibility vests of construction workers and the athleisure wear of the condo-dwelling urban upper classes, he went to the mouth of the Don River and filmed himself performing with the coffin. The resulting video interweaves that footage with other scenes that relate to the river.

In Chris's gallery installation, the video shares space with other works meant to reference the Don River's semi-natural milieu, including a wall hanging made of pieces of paper that Chris dyed using inks derived from plants he foraged from the Don River Valley. At the centre of the installation is the mirrored coffin itself. Inside of it, Chris placed 19th century maps of the Don River and other archival materials.

"The work is critically engaging with the Don River's revitalization," Chris says. "It questions to what end the revitalization is being done. Is it being done because it's economically viable? There's a critique of that in the work. But it's also meant to pose questions about how revitalization is enacted, and about the historical and material relations between the city and the lower river valley."

Brandon Poole's installation, titled Blind Pilotage, began with a serendipitous discovery. During a research visit to IMAX's Canadian headquarters in Mississauga, he happened to get contact information for a former IMAX employee who had saved a stash of film from the company's earliest days, in the 1980s.

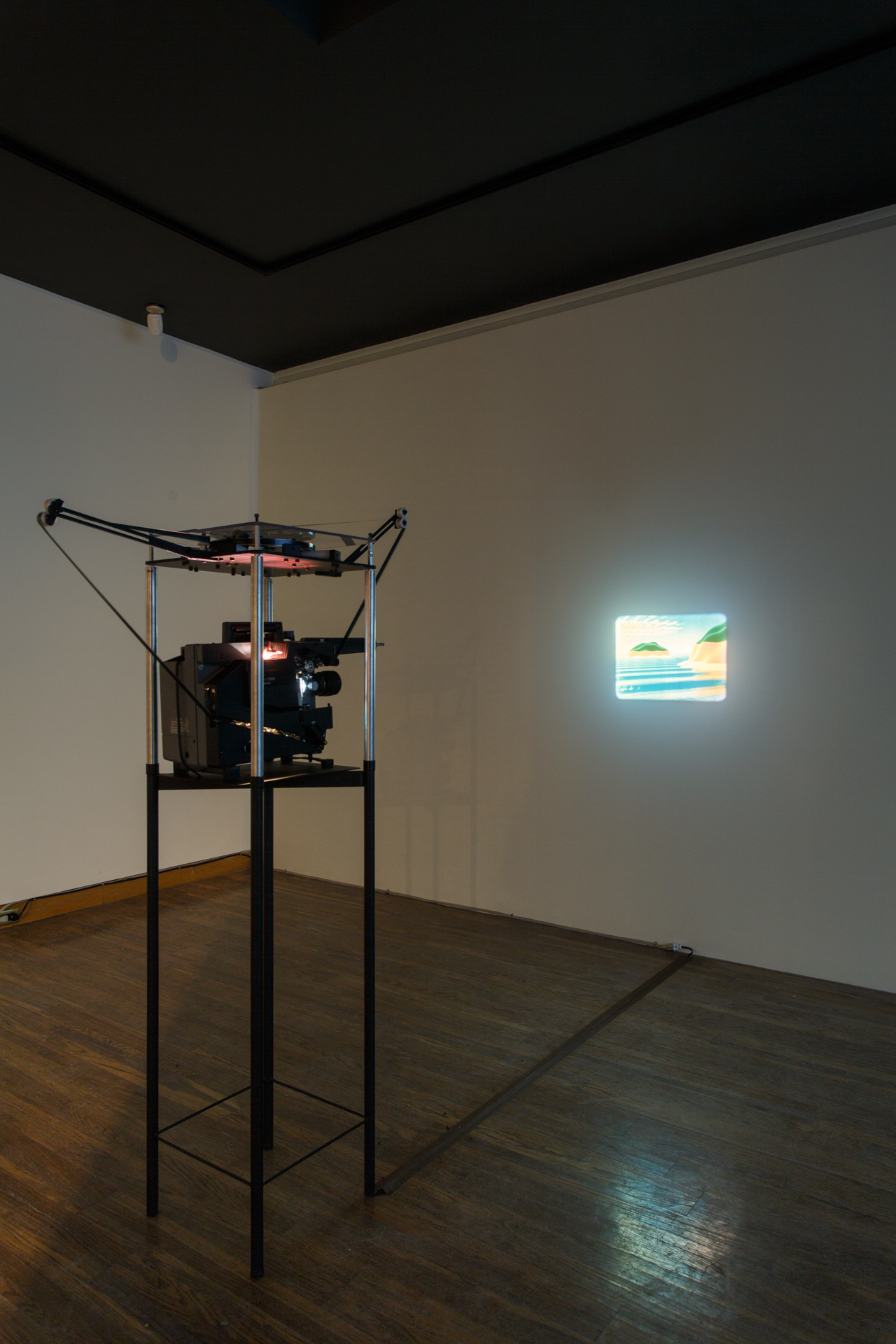

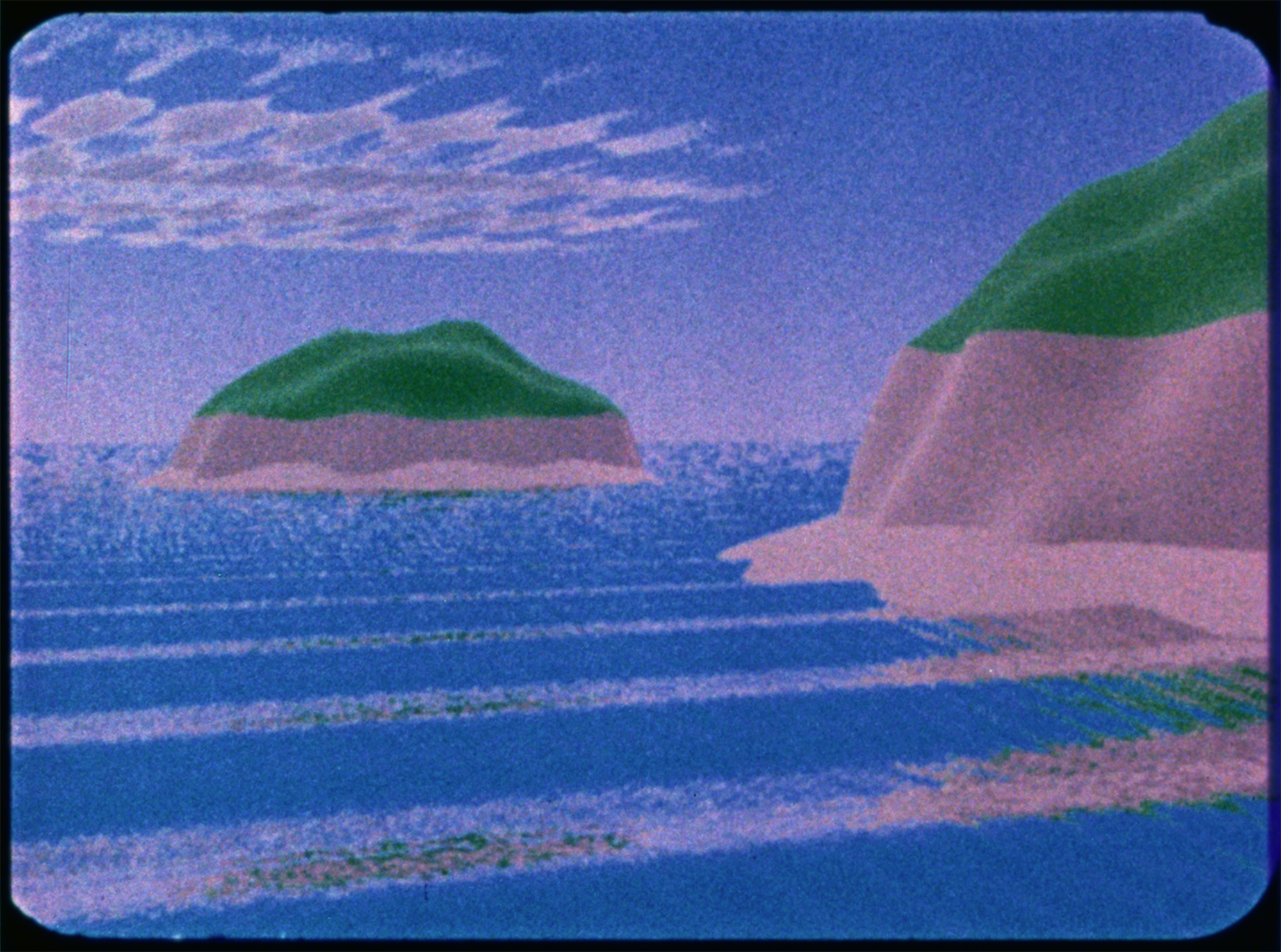

Brandon arranged to sort through the collection. Among it, he found a clip from Carla's Island, a short film produced in 1981 by a computer scientist named Nelson Max. The film, which shows waves lapping at the shores of a pair of islands, was one of the earliest (if not the absolute earliest) depictions of computer-generated water.

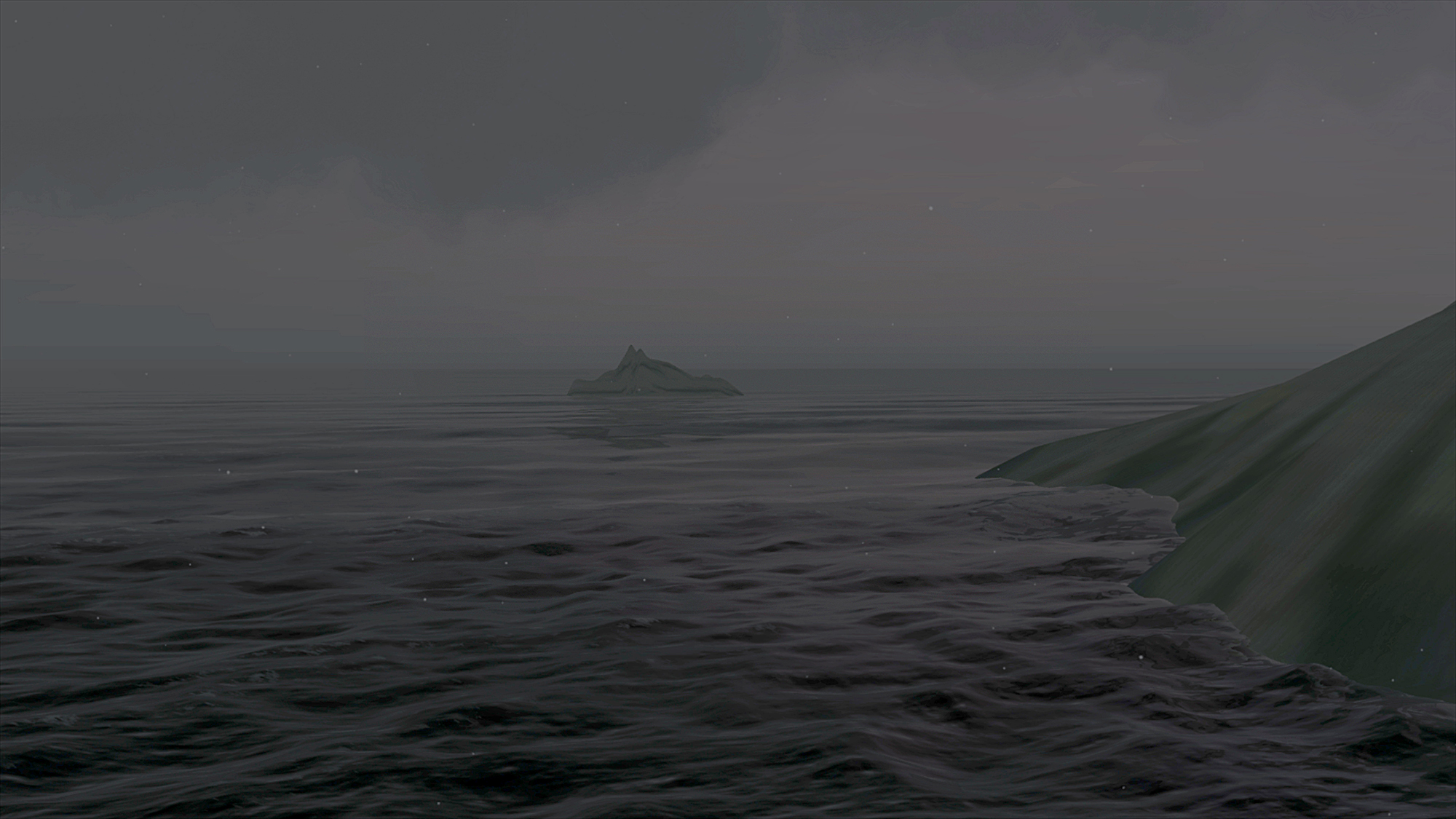

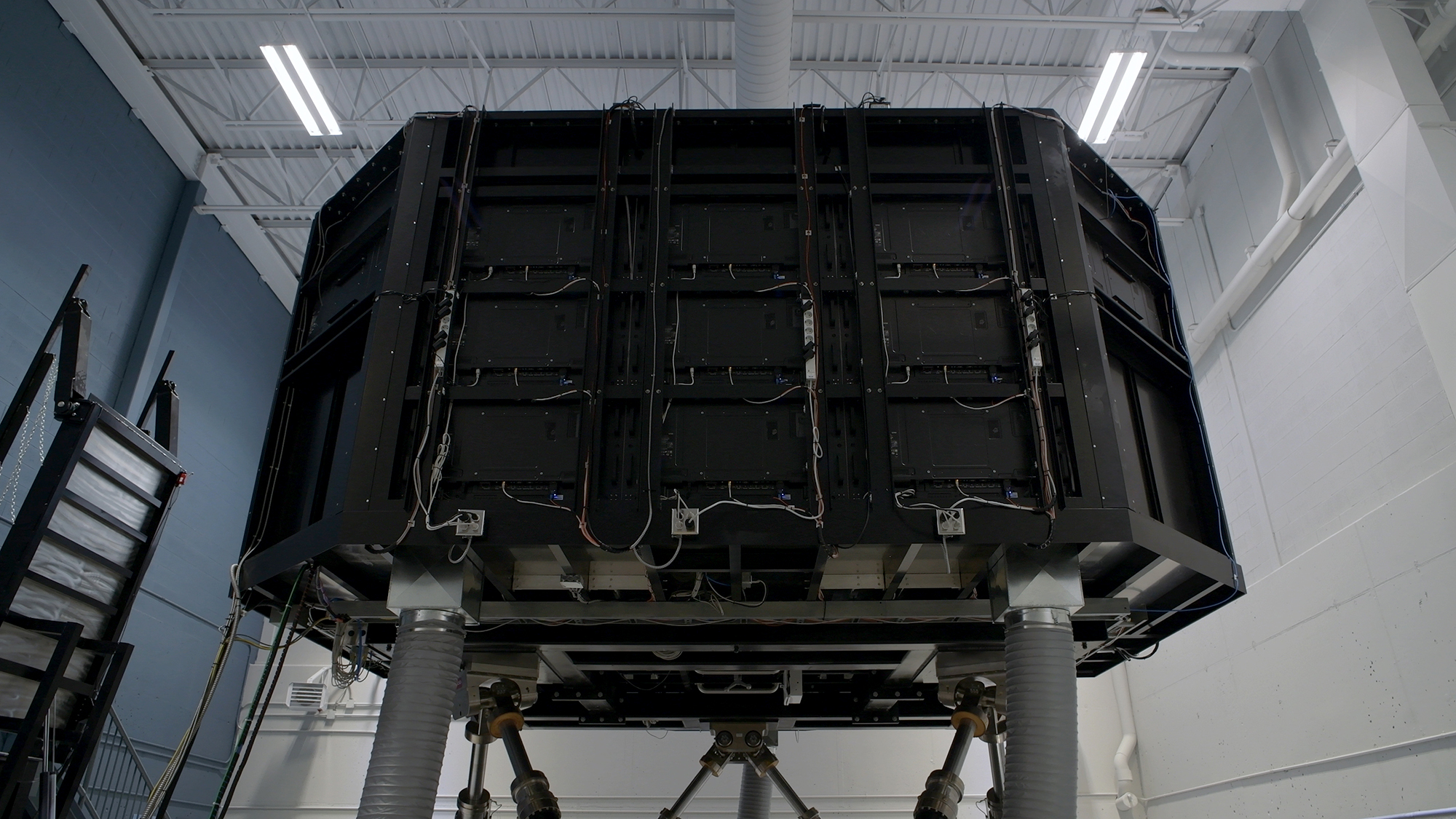

Brandon's installation juxtaposes a three-and-half-minute loop of part of Carla's Island with a much more recent instance of computer-generated water. For the latter, Brandon travelled to Memorial University, in Newfoundland, where he spent five days working inside the Centre for Marine Simulation's offshore operations simulator — a giant black box with a simulated ship's helm inside. The simulator accurately reproduces the feeling of being on a boat by using hydraulic lifts to simulate motion from waves and weather conditions. The system is used to train people in the safe operation of sea vessels.

For the purposes of his artwork, Brandon had a different goal in mind. Within the simulator's highly detailed virtual world, he created a replica of the islands from Carla's Island, with icebergs substituted for the original film's pleasant tropical landmasses. With that done, he captured high-resolution footage from both inside and outside the simulator. The resulting video projection takes up an entire wall of the art gallery, opposite Carla's Island.

"With the simulator, not only is it just a simulated image of water, it's simulating the motion of a ship on water," Brandon says. "So it's this further level of distance away from really being on the water." On the gallery wall, beside the simulator projection, an oil-lamp gimbal — a piece of equipment designed to keep a lamp upright as a ship pitches on waves — sways in time with the simulator's movements, as if to suggest an automated seafaring future that's still under construction.

There is one more component of Brandon's installation — and it's not necessary to go to the Art Gallery to experience it. Anyone with a decent computer can download and play The Far Far Splendour, a video game he created that (stay with us here) simulates the offshore operations simulator.

The inspiration for Jordan Elliott Prosser's installation, Assembly, came from close to home. His childhood home in Oshawa, Ontario, to be exact.

Oshawa was an auto-industry town for nearly a century — that is, until 2019, when General Motors ceased production at the local assembly plant. (A recent deal with workers may bring back some car production by 2021.)

"My parents worked at the General Motors Canadian corporate headquarters, which was in Oshawa," Jordan says. "And my grandparents before them worked in the assembly plant. I grew up within the auto industry, described by the suburban dynamic of living in cars and having this exurban house on a tree-lined street with a pool."

For his installation, he created a video about Oshawa that combines elements of documentary film, autobiography, and cinéma vérité. The video revolves around Parkwood Estate, the former home of Robert Samuel McLaughlin, one of the founders of Oshawa's auto industry and a one-time president of General Motors of Canada. The estate is now a national historic site, frequently used for weddings and film shoots. "There's this historical fetishization of the place, locked in history," Jordan says. "It's sort of like a shrine, in a way, to Oshawa."

The video also includes scenes from Cullen Gardens, a now-shuttered tourist attraction that once contained a miniature village with models of some Oshawa civic structures, including Parkwood Estate. Jordan found archival footage of the tiny village at the Whitby Public Library.

The bulk of the video is made up of scenes from significant sites in the Oshawa area, shot by Jordan as he travelled the city. In one instance, he put his camera in a shopping cart while he and his father wandered the aisles of a local Costco. "The film itself is a mosaic," Jordan says. "It's a portrait of Oshawa at this precarious moment in its identity. It's a town that's no longer an auto town. It hasn't been for a while. They closed the plant, so you don't even have that anymore as a last bastion of identity-making. I'm interested in why people hold on to particular points of their identity even as the hallmarks of it start to be eroded."

In the gallery, opposite Jordan's video screen, is an assemblage sculpture made from childhood objects he found in his mother's Oshawa basement, perched atop a neat cul-de-sac of beige, suburban-style carpeting.

The curatorial students

Yuluo Wei's exhibition, "if a turtle could talk," is a presentation of work by artists who use traditional Asian methods and materials to comment on Asian folklore. "I'm very interested in mythologies," Yuluo says. "Especially non-western mythologies."

Yuluo deliberately selected works that she felt would immerse viewers in this mythological world. The centrepiece of the exhibition is Earthly Delights, an installation by artist Ed Pien that looks like a round tent. Visitors are invited to duck into an opening in one of the tent's walls. Once inside, they're presented with a surprising display: the interior is covered in ink drawings that evoke scenes from Hieronymus Bosch's The Garden of Earthly Delights. Visitors can peer into tiny peepholes to see Pien's illustrations of otherworldly monsters.

In an adjoining room, Yuluo has installed works by Chinese-Canadian artist Xiaojing Yan. Mountains of Pines, a series of gauzy fabric panels pierced with pine needles, resembles the ink-stroked peaks of a traditional Chinese landscape painting. Behind the semi-transparent fabric is Far from where you divined, a series of sculptures — a deer, rabbits, a young girl — that the artist swabbed with lingzhi mushroom spores. The ear-shaped mushrooms, which are used in traditional Chinese medicine and are symbols of health and longevity, sprout from the sculptures at odd angles.

To tie it all together, Yuluo composed an original story — a fairy tale about a turtle who becomes lost in the human world. She'll be doing an online reading of the story on November 21. For details on how to join the reading, visit the Art Museum website.

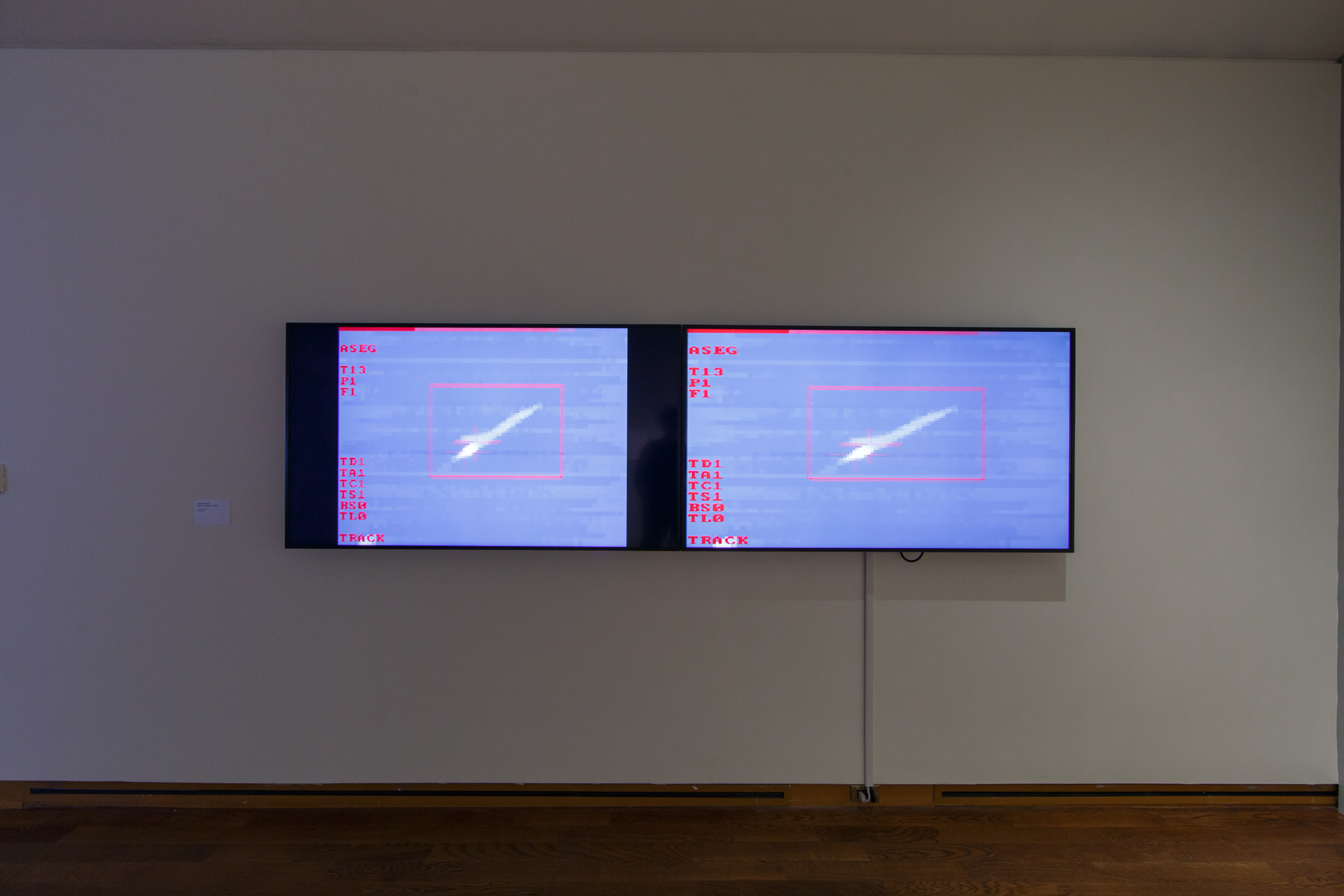

Fatma Yehia's exhibition, "Overt: Militarization as Ideology," presents a series of artworks that consider the concept of militarization — but not in the ordinary sense of the word.

Fatma is originally from Egypt, a country where military rule is an inescapable fact of everyday life. As she researched the concept of militarism, it occurred to her that Egypt's experience was only one end of a spectrum. Even in parts of the world where militarization isn't overt, military values and technologies still pervade societies. "When it comes to the western world, usually we don't see the destructive nature of military technologies," she says. "We only see the productive nature of them. But these two worlds are connected. It's the same technology."

One of the works included in the exhibition, a video installation by Harun Farocki titled War At a Distance, makes the connection between war and militarism explicit. The film, released in 2003, just as the United States was ramping up its second invasion of Iraq, explores the connections between US military facilities during the first Gulf War and modern factories that produce objects for use in everyday life.

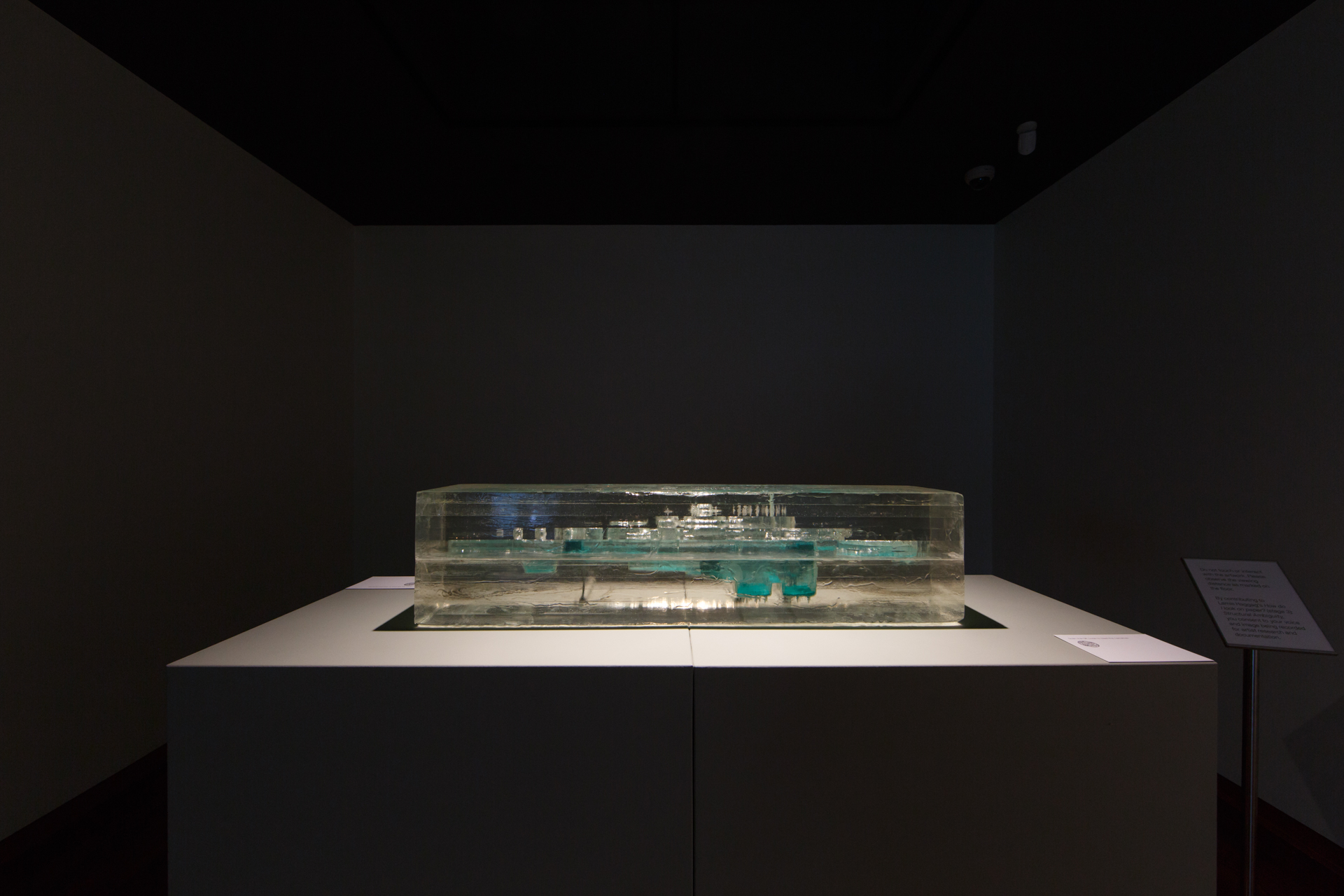

Structural Ambiguity, a work by Lamis Haggag that Fatma commissioned specifically for her exhibition, is a water-filled sculpture that captures words spoken by visitors inside the gallery. "Lamis is interested in how the military state has an impact on the use of language," Fatma says.

Hidden microphones pick up snippets of conversation from passersby and then run those word fragments through Google's speech recognition library. The sculpture then translates that speech into movements in its internal water reservoir. For Fatma, the connection to Google's artificial intelligence systems is a vital one. "Google collaborates with military and state security services," Fatma says. "And so Lamis was wondering about the purpose of Google's speech recognition library. What could it be collecting from us, and how could it be used in training AI programs?"

Xenia Benivolski's exhibition, "The exhaustive thought," is the first-ever solo show for Zanis Waldheims, a Latvian-born, Montreal-based outsider artist who died in obscurity in 1993.

"Zanis is an interesting example of how one is forced to communicate in nuanced ways as a result of migration or exile," Xenia says. "If you don't have the vocabulary, how do you communicate otherwise?"

Waldheims was a lawyer in Latvia. He arrived in Canada in 1952 as a postwar refugee and lived the remainder of his life in relative isolation, never seeing the family and friends he'd left behind in eastern Europe. In the absence of familial or personal connections, he became obsessed with philosophy, history, natural sciences, and linguistics. He amassed a library of books and filled their margins with notes.

Most amateur scholars would have stopped there, but Waldheims took things further. He developed a system for taking the ideas in the texts he was reading and representing them visually, in diagrams. He got into the habit of rendering these diagrams in brilliantly colourful, geometric, pencil-crayon drawings. To a casual observer, the drawings look like abstract visual art — but, to Waldheims, each piece represented a system of thought. He produced over 600 works in his lifetime, all or most of which ended up in the possession of one of his few friends, a man named Yves Jeanson.

To mount her exhibition, Xenia travelled to Jeanson's home in Laval, Quebec and negotiated a loan. The exhibition includes not only several examples of Waldheims' finished compositions, but also vitrines full of his notes and marginalia. A patient visitor with some knowledge of French can attempt to follow the entire process of distillation, from text to drawing.

"When you look at these drawings, each line and shade has a described meaning," Xenia says. "For example, in some of the drawings, the lower periphery of the drawing means 'reason,' and the upper periphery means 'imagination.' And if there's a diagonal line going up, it means 'future.' Others use different systems. The works are illustrations of philosophical concepts. And not just philosophy, but also biology, phenomenology, physics, and mathematics. He saw them all as parallel systems."

Photographs by Harry Choi.